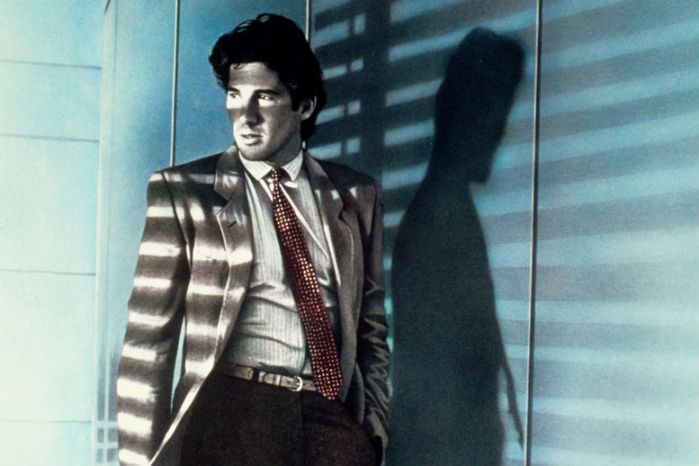

American Gigolo (dir. Schrader, 1980) turns 40 this year. The film is generally understood in terms of its significance in making actor Richard Gere and fashion designer Giorgio Armani household names. Its director Paul Schrader, producer Jerry Bruckheimer, and female star Lauren Hutton were already Hollywood stars in the ascendancy. My point here is that the film has a wider cultural importance in setting up a new template for the male sex object set within a shifting terrain of sexual mores, attitudes towards gender, and visual culture.

It is also important to compare it with Looking for Mr Goodbar (dir. Brooks, 1977), based on Judith Rossner’s best-selling novel of the same name, itself founded on the true life murder of school teacher Roseann Quinn who was stabbed to death by a man she met in a bar. Both films also precede Michael Douglas’s unholy trinity of movies encapsulating the mores and sexuality of the 1980s, epitomised by Fatal Attraction (dir. Lyne, 1987). What they share in common is their plotlines that, put simply, state that sex – or particularly pleasure-seeking promiscuity – leads to serious problems and, more likely than not in the case of women, death. Thus, Theresa Dunn leads a “double life” as schoolteacher and near sex “addict”, Julian Kaye (intriguingly called Julie) is a male escort, sex worker or “gigolo”, and Dan Gallagher is a successful married lawyer who “strays” with high profile editor Alex(andra). Dunn is murdered whilst Kaye ends up framed for murder. Interestingly, Gallagher is not “promiscuous” as such yet his breaking of the rules of monogamy at the height of the AIDS pandemic is sufficient to turn a simple affair murderous.

The first two films are the more interesting to compare for what also unites them is Gere, a gigolo in the second and – more implicitly – a hustler in the first. In both cases he is cast as a “good time boy” with the styled looks of an Adonis and an intense dislike of anything that ties him down. That particularly includes relationships and Theresa Dunn and Julian Kaye, whilst of opposite genders, are cast as equally psychologically “unhealthy” in their avoidance of emotional intimacy. Julian is eventually saved by the love of a good woman; Theresa is beyond recovery. The interplay of gender and morality is therefore critical as whilst Julian is disreputable as a gigolo, he can be redeemed by love and monogamy whereas Theresa is so morally aberrant her murder only becomes interesting precisely because of the sexuality that precedes it.

The moral boundary making of hustler and gigolo movies themselves has precedent, most markedly in Midnight Cowboy(dir. Schlesinger, 1969). Part buddy movie and part unprecedented expose of the seedier side of life in New York City life, the film politically and morally underlines the idea that nothing good comes from prostitution. The sex scenes are either comedic or violent rather than erotic whilst wannabe male prostitute Joe Buck (Jon Voight) is presented as inept and confused as much as he is sexually attractive. Emblematic here is his rather outdated cowboy outfit which he discards at the end of the movie symbolising his break with his “aberrant” past and his embracing of emotional support for his ailing buddy “Ratso” Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman) but it is all too late as Rizzo dies on the bus.

There are further layers here relating to questions of sexuality. First, as is the case with Midnight Cowboy, each of these films is liberally littered with negative views of male homosexuality. They both contain various storylines set within the gay scene and involve gay or bi-sexually identified characters that are key in the “downfall” of their straight counterparts. Thus, Dunn is killed by a repressed homosexual whilst Kaye is framed by an openly gay pimp. The casting of gay or lesbian characters as morally dubious murderers and “psychos” is notorious within Hollywood movies past and present from Cruising (dir. Friedkin, 1980) to Sharon Stone (cue the Douglas trilogy) as a bisexual/lesbian serial killer in Basic Instinct (dir. Verhoeven, 1992) and the ambiguous serial killer at the centre of The Silence of the Lambs (dir. Demme, 1988), a trope that goes all the way back to Hitchcock’s Rope (1948).

More ambivalently, each of these movies also relies heavily on their sexually infused disco soundtracks. Whilst American Gigolo is famous for its flavour of the moment pop band Blondie’s hit “Call Me”, it is also dominated by music of Giorgio Moroder whose work also underpins some of the sounds of Looking For Mr Goodbar, itself otherwise punctuated throughout by the likes of Diana Ross and Donna Summer. Moroder is famous for his collaboration with Summer – themselves icons not only of disco rather, more to the point, gay disco. What we have here is a curious mixing of messages as audiences are encouraged to empathically engage with characters and experiences through the disco-infused soundtracks whilst simultaneously they are warned of the dire consequences that will ensue if they are too seduced by them via the plotlines.

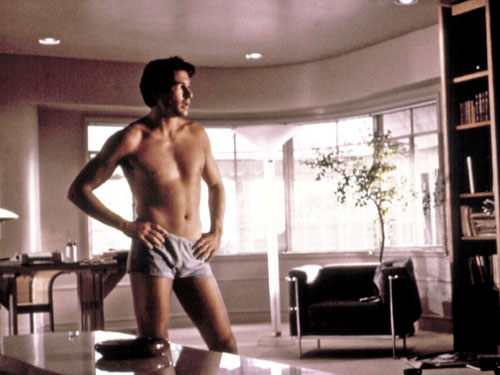

Whilst the moral boundary reinforcing role of all of this is not in doubt and well documented by the likes of Richard Dyer, the question in the newer American Gigolo becomes its relationship to the homoerotic Gere. Although little ambiguity surrounds the actor himself, his roles at the time are profoundly sexually abstruse. Tony, the hustler of Looking For Mr Goodbar is heterosexually promiscuous yet when presented doing press-ups in a jockstrap is equally coded for a far more homosexual appeal whilst his exercise and fashion regimes in American Gigolo register him as stereotypically gay. Thus, the famous scene of him laying out his endless clothes and coordinating shirts, ties and jackets is not only crucial in promoting the reputation of Giorgio Armani rather it assimilates Julian within a far “gayer” aesthetic. Yet the most crucial factor here is Gere himself. Whilst soon to be famous for his “looks so good in uniform he could turn a straight man gay” scenes in An Officer and a Gentleman (dir. Hackford, 1982), given the increasingly homosexual associations of uniforms themselves at the time (cue The Village People), it’s actually Gere’s body that becomes critical. Gere is shown exercising next to naked and fundamentally accords to an increasingly dominant aesthetic of tall, broad shouldered muscularity and athleticism.

Although Looking for Mr Goodbar and American Gigolo were moderate box office successes, they were too left field, too morally ambiguous, to go mainstream in their defence of disco. The game changer, and important point of comparison, here is Saturday Night Fever (dir. Badham, 1977) – a film so successful, particularly in terms of its soundtrack, it broke records as well as made them. It also made John Travolta a household name. Its success comparative to the others mentioned here is worthy of some questioning in itself. Of key significance is the fact that Tony Manero, unlike Julian Kaye, is neither sexually ambivalent nor making money from it. Saturday Night Fever, for all its disco hedonism, is in essence a and a tale of aspiration and hope whilst in poverty. Manero like Kaye is, however, both consumerist and embodied. His white suit is now more famous than he is; whilst his hair combing and bum wiggling sexually objectifies him. Travolta’s body, though occasionally seen in briefs, is primarily sexualised through the clothes – the tight trousers, white suit, satin shirt, etc. – and Manero, unlike Kaye, has an almighty Italian American back story of warring generations and religion to match. Julian by contrast is not only so sexually ambiguous he becomes Julie; he floats like a tabula rasa of character less mystery throughout the film. One cannot identify with him or even really aspire to be him as one does not know him to begin with. Thus, the desire the audience has for him is primarily consumerist rather than character driven. The same can hardly be said of dead-end hardware shop working and family battling Tony Manero. It is this characterisation process and working classness that neutralises the sexual ambiguity into something wider audiences can aspire to and idolise.

Although only three years apart, the styling of the two films seems almost worlds away. This is partly due to geography as both Saturday Night Fever and Looking For Mr Goodbar are set in New York City whereas American Gigolo is located in Los Angeles yet more widely relates to a shift in visual culture and aesthetics. Whilst the former two films mostly work within a field of realism – Dunn’s dirty and messy apartment or the crass posters of Manero’s late teenage bedroom – the latter sets up a far more aspirational, stylised and consumerist landscape set around the lighting of Kaye’s apartment filtered through louvered blinds, his Mercedes coupe on coastal roads, and the sun loungers and swimming pools of the rich and famous. This comes across as far more contemporary in its magazine like aesthetics than either of the other two films that bathe in a nostalgia for smoke and whirling disco balls. But within this again it is Gere that is key as an entirely different kind of sex object from Travolta – naked yet dressy, ambiguous yet characterless – in postmodern terms, a far more free-floating signifier of consumer desire.

Sexual objectification of men within film is of course as old as film itself. Thus, whilst Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, Humphrey Bogart were all cast as leading men that could make a woman swoon, they primarily kept their kit on. The rise of a more rugged masculinity in John Wayne and the western genre was equally for the most part clothed. Similarly, the likes of Redford and Newman in films like the number one hit Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (dir. Hill, 1969) or The Sting (dir. Hill, 1973) are barely seen with anything less than their collars undone. Even Travolta’s later hip wiggling dancing in the stratospherically successful Grease (dir. Kleiser, 1978), although revealing, is not exactly naked. Gere by contrast gets his kit off entirely to the point of doing full frontals. Whilst not entirely “ripped” to contemporary standards, his athleticism and looks echo a Greco-Roman ideal down to the cut of his rather lush hair. This is not just fashion, though that is a factor, it is the shifting of Gere into the increasingly ambiguous double or dual marketing of the male body to appeal to a gay and straight audience alike.

By the mid-1980s this was dominant in the selling of everything from Levi’s jeans to Calvin Klein underwear and from music to film. Thus, Gere’s successor was the diminutive but equally athletic and similarly styled Tom Cruise in “the more than a bit sexually ambiguous” Top Gun (dir. Scott, 1986), cue more locker rooms and more uniforms. What informs the importance of American Gigolo forty years on, then, is not the spectre of sexual pleasure in male, or even female, form – something still unresolved in the utter horrors of 50 Shades of Grey (dir. Taylor-Johnson, 2015) – rather it is the male form itself and the requirement that any actor in any role should now look good with his shirt off, a factor now so overwhelming that actors have to put their shirts back on to be taken seriously. So Chris Evans – an actor with a torso so aesthetically perfect it could make Michelangelo weep – in an attempt to move out of a stereotyped rut has started putting his clothes back on, whilst never a lightweight to begin with Daniel Craig quit being Bond having had to become the one that has to emerge from the waves in his swimming costume. Whilst there are other turning points along the way – Pitt’s “obliques” in Fight Club (dir. Fincher, 1999) – it was Gere’s shift towards an Adonis driven body beautiful that remains the key driver in this.

The passenger sitting alongside this, however, is commodification. Such physiques require training that in turn depends upon product and gym membership yet, more importantly, they are set and displayed within contexts of high conspicuous consumption so that scene of Julian coordinating his clothes requires a naked torso to dress AND an apartment full of highly aspirational clothes and props. Moreover, within a mere twenty years, Julian Kaye’s laying of clothes would become the penthouse glass, narcissistic and commodified grooming ritual of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho (dir. Harron, 2000) or the controlled, steel grey apartment meets porn set of Brandon Sullivan in Shame(dir. McQueen, 2011) – or, in short, the point where body meets mirror in the guise of a now well-trained consumerist gaze.

Of course, the other, and final, so-obvious-you-almost-miss-it, difference here is that Kaye, Bateman and Sullivan alike are not just naked and consumerist objects of desire but men who are alone. There is an interesting gear shift here not only forwards rather in reverse to the figure of the gun-slinging cowboy who rides into town, causes all sorts of commotion, and then rides out again – the plotline of countless westerns. Yet the shift forward is towards something far more middle-class, consumerist and aspirational – two factors that were then blended, to overextend the metaphor, in the aptly named Drive (dir. Winding Refn, 2011) the story of a stunt driver turned hero dressed in the most well-cut jeans you have ever seen. Whilst Gosling’s nuanced ambiguity would continue American Gigolo’s legacy, Gere’s own Hollywood stardom was set to decline into debates about Buddhism and Tibetan politics. Prior to this, he had one last hurrah as sexual hero of the hour when he inverted his gigolo status to become the trick that hired a prostitute and lost all his sexual ambiguity along with the pigment of his hair in Pretty Woman (dir. Marshall, 1990). There are two factors of note here. One, that Gere had become older, and sexual ambiguous naked male bodies have to be younger; and two, that the plotline of Pretty Woman plays into an altogether earlier and more traditional male trope namely that of the Hollywood idol, one that a certain Mr Clooney then took over for himself. So, what we have here is a crossing of lines and travels of several differing idealised forms of masculinity in film, driven forward and combined in various ways; yet it was Gere’s quixotic shifting of desirable masculinity into a newer, barer and more consumerist ideal that remains axiomatic in cinematic history.