Kate Bush was recently awarded with a Fellowship of the Ivors Academy. Whilst arguably overdue, the award recognises Bush as primarily a writer and creator of music rather than as some kind of pop star and my point here is that she is indeed of the most “writerly” of artists. Her career consists of ten highly original studio albums, a live album, a greatest hits, and two pathbreaking multimedia live shows. Although perpetuated as “reclusive” across the media, her output is neither as small as some nor as inconsistent as many of her contemporaries, male and female, in the standards it hits. It seems appropriate, then, to give it the kind of “writerly” review it deserves.

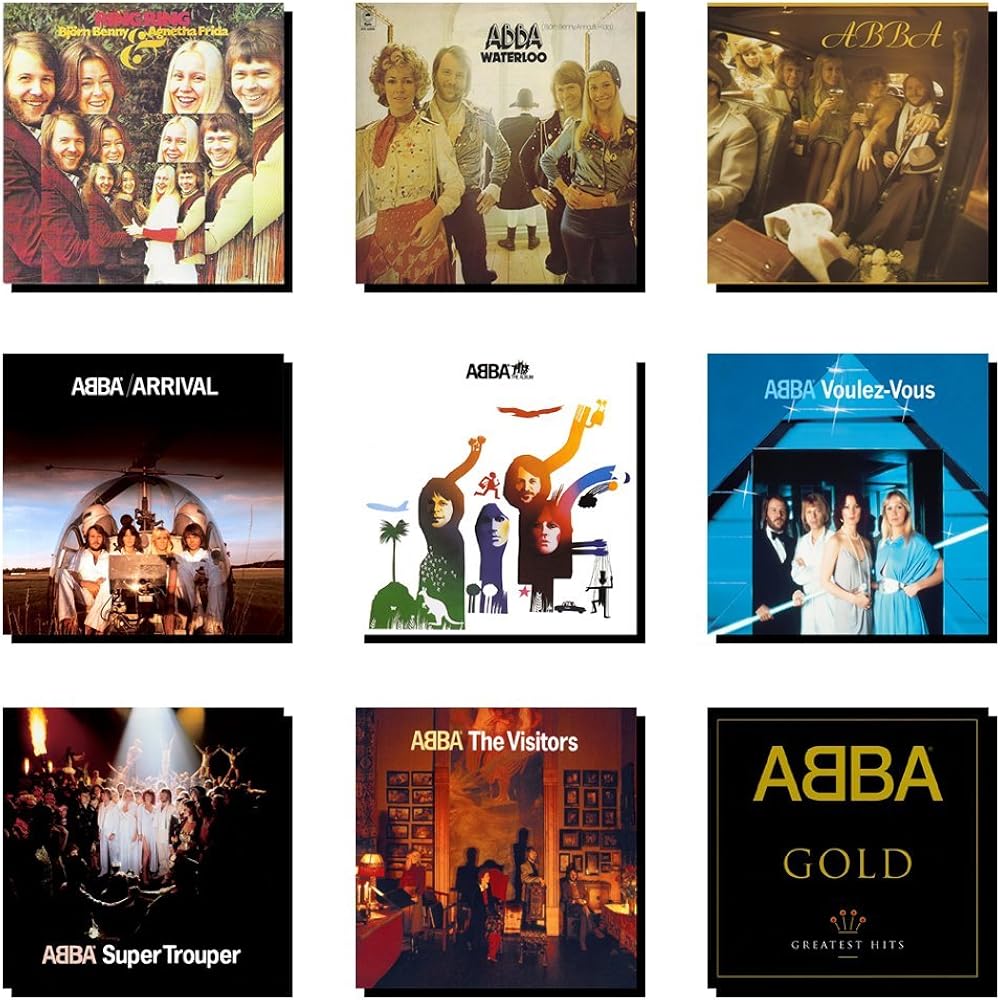

Forty years ago, Kate Bush would become the first woman to have a solo self-penned number one album in the British album charts. Given the remastering of Kate Bush’s entire back catalogue, it is easily forgotten that 2018 marked the fortieth anniversary of her arrival on the popular music scene cartwheeling around in a white dress on video or swirling in black velvet on Top of the Pops. Yes, those were the days. I’m sure I am not alone in remembering the first time the stylus hit the vinyl of The Kick Inside. Not surprising then perhaps that these were tagged remasters “in vinyl”. As the whale song gave way to an imploring of “does it really matter as long as you’re not afraid to feel” above piano and plunging bass line, one could but stand there and think (or feel) what the hell was that… yet soon enough you were plunging like Alice down a hole into Wonderland… “to be in love, and never get out again” as the woman herself might say. Move forty odd years forward and listening to those opening bars of “Moving” it is no easier to deconstruct quite what did happen or quite what hell that was. It’s worth remembering that at the time there were few women in the pop world who were not just front women singers but also songwriters. Everything about Kate Bush is writerly, she is – and was – from the get-go a writer, a creator of worlds, whether with her music, her lyrics, or to some extent her videos. This was, and is, art not pop. And then of course there is that voice. Love it or hate it, the remastering brings it centre stage from the sometimes-foggy vaults of the earlier mixing. Her detractors criticised her for sounding too young, but she was young – many of the compositions from not just this but the first three albums were done when she was a teenager and, in some cases, even earlier (the lyrics for The Man With The Child In His Eyes were allegedly first written at eleven on a den wall). Listening to these recordings now, one is struck not just by the pitch she hits but by the power of her voice, those swirling octave ringing vowel twisting howls and screams, delicate one minute then unleashed to the chandeliers the next. Wuthering Heights is a case in point. The voice comes as if from nowhere and pitched solo against a piano then battles full throttle with a band and an orchestral backing. She is at her most impressive vocally when things get stripped back to her voice, a double bass and the piano on songs like Moving, Feel It, L’Amour Looks Something Like You or indeed The Man With The Child In His Eyes and comes rather unstuck when she attempts to “rock it up a bit”. James And The Cold Gun remains a horrible attempt at rock ‘n’ roll and others still misfire. Them Heavy People really needed the live treatment and Kite, whilst funky and full of vocal gymnastics, is resolutely just plain silly. She would also later complain that her producer Andrew Powell suggested too much fantasy and take on full artistic and production control herself in under five years. Yet for these occasional failings, The Kick Inside is stuffed full of the compositional craftwork that would make the likes of Andersson and Ulvaeus, whom she toppled from the number one spot or Elton John, whom she worshipped, clap with pride. Songs like Strange Phenomena are – stripped of their strangeness – just finely made pop songs. The remastering does some of this credit as the percussiveness and Bush’s own piano playing ability come to fore. Over forty years on and The Kick Inside remains one of the most startling and arresting, yet also accomplished, debuts of the modern pop era.

Her second long-player Lionheart is well-known not to be one of her favourites, the songstress herself often claiming it to be a rushed job. Whilst her attempts to get heavier and more percussive are hit and miss, it’s more maligned than it deserves to be and the remastering goes some way to levelling things out – Don’t Push Your Foot On The Heartbrake still rolls rather than rocks but loses some its original harshness whilst the gentle Renaissance flutters of the title track are far more distinct, foreshadowing her tribute to her son Bertie on Aerial. Her song writing is also better than it is often made out to be – Kashka From Baghdad remains a gorgeous eastern influenced paen to outsider love now given even lusher brushstrokes from her brother Paddy’s instrumentation, forerunning the kind of material that would arrive on The Sensual World over ten years later. The theatrics are a mixed blessing – Coffee Homeground frankly still sounds a bit silly – but her on stage dramas captured in the two lead singles Hammer Horror and Wow enchant as much as they used to whilst that voice is given more of a leading role on most if not all of the album.

Never For Ever would prove to be a first on several fronts – her first number one album and the first number one album in the British charts penned and performed by a woman – but, more importantly, her first attempt at producing and her first go at “serious artistic credibility”. She had already collaborated with Gabriel on his highly acclaimed third album and his influence becomes clear here, credited directly for “opening the windows”, and she now co-produces. It’s a curiously mixed bag overflowing with good ideas, not all of which come to fruition, and Janus-headed. In the middle, we have Blow Away – a piano based homage to engineer Bill Duffield who tragically fell and died on her Tour of Life. Half of the album looks back to her earlier attempts at melodrama and half of it looks forward to the greatness that would come to be. At its best, and closing, stages this album is up there with her very finest. Army Dreamers makes ingenious use of the Fairlight synthesiser to mix the cocking of a rifle into the lilt of its funeral march whilst Breathing remains a five and half minute epic, and self-proclaimed “mini-symphony”, upon the theme of nuclear war told from the point of view of an unborn baby. By this time, Bush’s ability to not only go down rabbit holes but conjure up entire new worlds was coming into full view and would only be matched in its bravura by the best of Hounds of Love and Aerial much later. The early parts of the album fare well here – clearer vocals, more space in the instrumentation (at least in the 24-bit version), and a toning down in the harshness. Babooshka is super crisp while Delius chugs away with delicacy yet it’s on the wobbly melodramas in the middle and later bits that the remastering really starts to matter. The theatrical percussion of The Wedding List really pops and the song starts to sounds less like Tarantino and more like the theatre she might have intended it to whilst Violin similarly benefits from mastering that seems to strip it back to a more “live” sound though there is still no escaping that it’s madder than a box of frogs. Bush has long been awfully good at pent-up bodice rippers of which The Infant Kiss is a case in point tingling with the sexual tension of The Innocents film version of the Henry James novel that inspired it. Egypt was always over-ambitious – an attempt to produce an audio commentary on the extreme contrasts of a country – yet it does sound less forced here. Breathing however remains her first true masterpiece of layering, production and rhythm – a lilting piano and bass mimicking a hospital ventilator overlaid with something that sounds altogether more like the act of creation itself before the unborn foetus starts bawling its head off for its Pink Floyd rock opus moment.

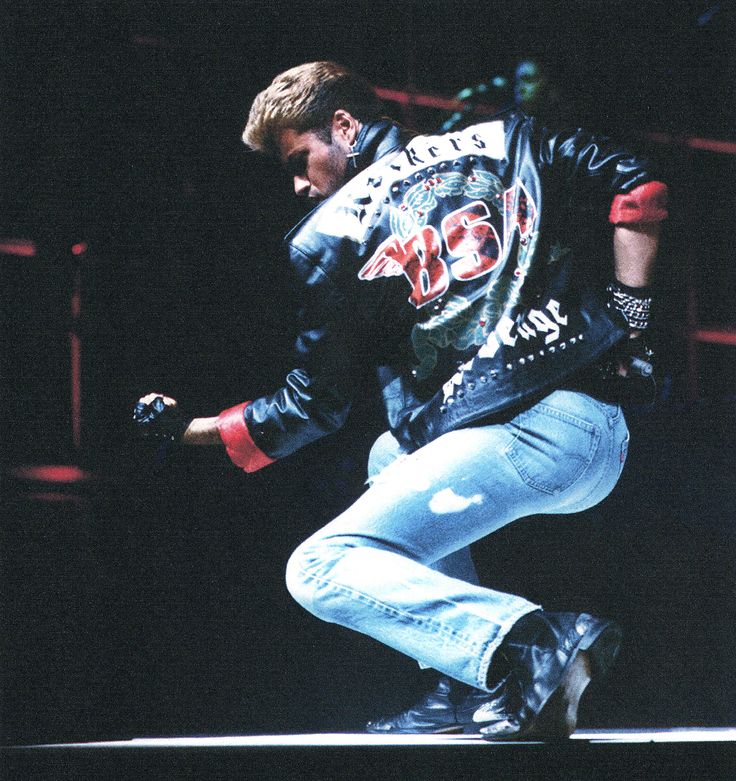

The Dreaming remains the album that separates the real Kate Bush fans from the merely wannabes. Starting with the full-frontal drum assault of Sat In Your Lap and ending with a chorus of braying donkeys, what she jokingly calls her “she’s gone mad’ album is seen by some as her truest masterwork whilst others remain completely foxed. Of interest here is the sense in which the remastering itself regains its capacity to shock for few, if any, accounts of the significance of this record recognise equally both its bravery, its claustrophobia, and its fury. Bush, who had long been stereotyped as an elfin female fantasist, was now desperate to be taken seriously – thus she studiously avoids any kind of balladry, turns her voice upside down and inside out to put some “balls” into it, and bangs drums – literally, symbolically, and loudly. Sonically at least, this record is astonishing, and the recent studio tweaking regains its initial glory as the elements – particularly vocally – are separated out more clearly the effect of which, on occasion at least, is all the more scary. Leave It Open is a case in point as the “weirdness” is indeed let in though a multitude of voices and, whilst her earlier attempts at melodrama were hit and miss affairs, here she finds her feet with jaw-dropping aplomb. Whilst the likes of Pull Out The Pin gain clarity, the real excitement comes in the second half as “the abo song” aka The Dreaming becomes all the more visceral in its evocation of aboriginal dreamtime spookery – all breathy demons, rumbling didgeridoo, and a farm yard of animal sounds so lifelike you really could be having trouble sleeping in the Australian bush at night – which then gives way to the imploring yet rollicking ceilidh and dialogue of Night of the Swallow. The Dreaming is indeed a dark record. All The Love is an intense a psychodrama of when no-one’s answering the phone as it gets yet she manages to accomplish it with a choirboy and the messages of friends. As if that were not enough Gothic horror we get Houdini’s relationship with his wife who would “pass the key” then watch on in horror as her husband tried to escape from locked chains in a tank of water and The Shining inspired Get Out Of My House where, rumour has it, she spent six weeks trying to get the drums to sound like slamming doors. The anthropomorphised “human house” drama created here and elsewhere is, to say the least, intense ratcheting up the painful and the furious to alarming effect. Again, her vocals come to the fore which makes the whole thing sound less like an eighties production piece and more like the visceral emotions of a singer-songwriter wrestling with her own demons. Thus, if there is one record in the Kate Bush canon that fans wanted to her re-done, and done like this, it is The Dreaming.

For most, though not all, Hounds of Love still stands as Bush’s masterwork. It is interesting to question why. Whilst providing her with her biggest hit since Wuthering Heights in Running Up That Hill along with the more commercial ammunition of side one, it is perhaps side two’s concept piece The Ninth Wave that is core here. In essence, though, this remains a mystery. On one level it tells the tale of a girl shipwrecked and left in the water at night not knowing if she will survive to the morning yet it is, as it were, what goes on underneath the surface of the water that intrigues here – seen by some as a story of reincarnation or other religious conversion – or more simply a work of creative imagination as Bush herself has alluded to little more than a fascination with the desperation of the situation she creates. Altered states of psychological distress dominate much of her work, both early and recent, and none more so than here. However, the story itself is of less import than the gamut of music gear shifting that gets crammed into less than twenty eight minutes as piano gives way to synthesised ice and then a wake-up call via a multitude of voices into drums overladen with Catholic prayer and witch trials that then suddenly transform into the clunking mechanisms of a clock, the clarion call of an Irish ceilidh, her brother’s poetry, and finally a male voice choir. Much as The Ninth Wave might represent some kind of unknown spiritual or psychological journey it is its musical journey that really matter and impresses. It’s freshened up here of both the earlier difficulties in balancing out all the natural elements at one end with the tendency to sound like an eighties experiment in digitised studio trickery on the other. The instrumentation sounds all the more natural on say Under Ice whilst Waking The Witch is less bass heavy and more percussive yet it is the vocal complexities of Hello Earth that benefit the most as Bush herself sounds as live as the choir she seeks to showcase. Much of the remastering on her “eighties” work is a triumph of digital clarity juxtaposed with the naturalness of something more analogue. That leaves the hits of side one to sort out and it is the title track that stands out here. Whilst The Night of the Demon horror movie inspired tension of the original recording was guilty of a galumphing drum rhythm dominating everything here it fights for centre stage with those wonderful violas. Equally her uncommonly loud rhythm tracks are ratcheted back a bit, and to better effect, on both Cloudbusting and A Deal With God (to give Running Up That Hill its proper title). Running Up That Hill would run all the way to the top of the charts thirty seven years later in the wake of its use on the sound track on the US TV series Stranger Things. It remains both a haunting and genius piece of songwriting on the theme of struggling intimate partners trying to “swap places” that appears to speed up through the arrangement and production to somehow “run” when in actuality it does no such thing. Cloudbusting meantime becomes a typical feat of master story telling here centred on Peter Reich’s A Book of Dreams. As many fans have noted, when Bush reissued the album on her own Fish People label a while back, she ditched the album recording of The Big Sky in favour of the single mix. Whilst it’s arguably a tad more percussive, particularly at the start, it’s difficult to know quite why she favours it and it would have been nice to see the original revisited. Nevertheless, she would knock Madonna off the top spot and Hounds of Love would prove a hard act to follow.

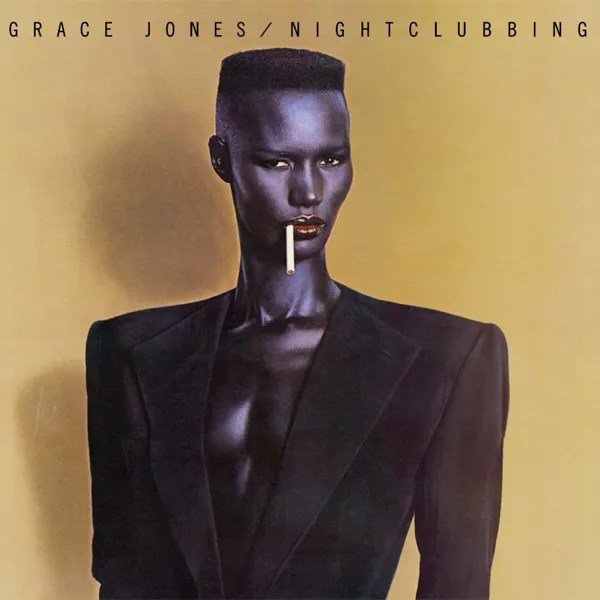

Whilst The Dreaming and Hounds of Love had showcased Kate’s increasingly dramatic and indeed cinematic talents, The Sensual World would set out to do something different. This in itself is a credit to her intelligence and, moreover, diligence as the easier option would have been to try and knock out Hounds of Love two. In an interview to accompany The Sensual World’s video single releases she discusses wanting to find a more “feminine” energy and the album is somehow her most “female”. It is noteworthy that she has rarely worked with female artists with the notable exception of here. Soon after receiving my copy, I played it to a Turkish friend of mine who did not know her music so well yet was entranced. For what defines this “female-ness” is something approaching an eastern, or even oriental, reverie on the sensual and emotional. This is symbolised in her use of the Bulgarian female singers The Trio Bulgarka whose traditional choral harmonising is blended with Bush’s own vocals to devastating effect on occasions. Whilst Yanka Rupkhina is, in one particularly bold move, given license to battle it out for supremacy with an electric guitar (Dave Gilmour’s no less) on Rocket’s Tail (the title a play on fireworks and her cat) it is on Never Be Mine that this vocal enmeshing reaches its true crescendo, a lush tremulous song exploring the pleasures and pains of human emotional and sexual intimacy. Indeed, much of this record explores “the thrill and the hurting” encapsulated in what is overall a very touchy feely set of songs. Whilst the rhythmic backing of Love and Anger or the dark disco of Heads We’re Dancing echo earlier styles, almost all of the songs here strive for less drama and more sensitivity. The title track is a case in point. Despite a multi-layered backing of drums, bass, bouzouki, uilleann pipes and whips (!) the overriding effect is of Bush’s quivering vocalising of “yes” in mimickry of Molly Bloom’s unpunctuated stream of consciousness at the end of Ulysses. Her frustration with not having permission to use the original words in Joyce’s novel would lead to her re-recording the song on Director’s Cut over twenty years later when the rights were finally hers. Curiously, she would also strip out the song’s lush layering and completely rework and rewrite another of the record’s highlights This Woman’s Work. Here it remains the short yet searing and poignant tale of a husband’s regrets whilst waiting outside his wife’s delivery room, originally written for the John Hughes film “She’s Having A Baby”. Other parts of the album are no less vulnerable yet visceral in their explorations of childhood. The Fog in a watery allegory on emotional “letting go” evokes the fear of “the day I learned to swim” replete with her father’s voice over; whilst Reaching Out evokes an even more infantile sense of touch. Whist it’s true some of the production in its more upbeat places still sounds a little stuck in the 1980s, all of these songs benefit from a dusting down to highlight their brilliance and The Sensual World remains one of her most underrated records. No, it was not Hounds of Love two – but that was precisely the point.

Bush’s problems, both personal and professional, with The Red Shoes album are well-known. To begin with, this vinyl release is the third time she has attempted to improve it as seven out of the twelve tracks here were substantially reworked for her Director’s Cut and the original album was remastered once already from the analogue tapes. The mastering here is unquestionably the best of the bunch adding clarity and space to the instrumentation and vocals but sadly the problem remains the album itself. It is often overlooked that most of Kate’s work, even when it sounds intensely personal and emotional, is written from the point of view of a persona, or an idea, around which she creates an entire world. In addition, these worlds are often coordinated into some kind of thematic vision that then constitutes an album. The problem here is that neither of these things really happens. Also, as anyone who was at her fan convention in 1990 knows, there was a loose intention post-The Sensual World to tour again given the increasingly long periods of gestation spent in the recording studio. Whilst the tour would not happen and time would be spent on a creating the mini-movie of music videos The Line The Cross and The Curve instead, best described as “a load of bollocks” (that’s her words not mine), this does account for one dimension of The Red Shoes namely is its attempt to sound more straightforwardly like a pop record. Indeed its miscellany of bangers endears it to some of her fans. The lead single Rubberband Girl is a prime example of this tendency as is the near 80s disco of Constellation Of The Heart and the soul funk collaboration with Prince on Why Should I Love You? Radio One at once stage started playing this particular song as part of its own playlist – yes, it really is that bad. The difficulty is that none of these songs really work as, whilst Kate has demonstrated an ear for a melody and a hook or two over the years, commercial she emphatically is not. A second dimension is a continuation of The Sensual World’s eastern and this time Madagascan influenced musical styles in such numbers as Eat The Music or The Song Of Solomon. This is more effective, particularly on Lily and the title track, inspired by the Powell and Pressburger film, yet the differing if not clashing styles reveal a lack of any clear focus or direction. Underlying the entire record however is a third, more lyric-centred dimension. This is her most personal record and, more to the point, she sounds in emotional pain for much of it. When not trying to observe relationships from further afar, the overriding tone is one of melancholy which informs the fan favourite Moments of Pleasure as well as And So Is Love and the closer, the Procol Harum influenced You’re The One. Whilst exact details remain unknown, it is no secret that she split up with long-time partner and bassist Del Palmer and that her mother Hannah died during the making of the record. In addition, it is far and away her most religious record invoking the biblical Song of Solomon, literally, and Lily, a prayer invoked/dedicated to spiritual healer Lily Cornford; as well as what can only be called mysticism on the Gabriel-esque Big Stripey Lie where she alludes to names being called by “sacred things that are not addressed or listened to”. Such personal losses clearly present particular difficulties for a form of music making such as Kate’s which is centred on deep emotional exploration and working – quite literally – in the confines of a close home and family network. However, one ultimately has to forgive the misfires here and allow her the space to recover, though perhaps no one could anticipate that would take twelve years…

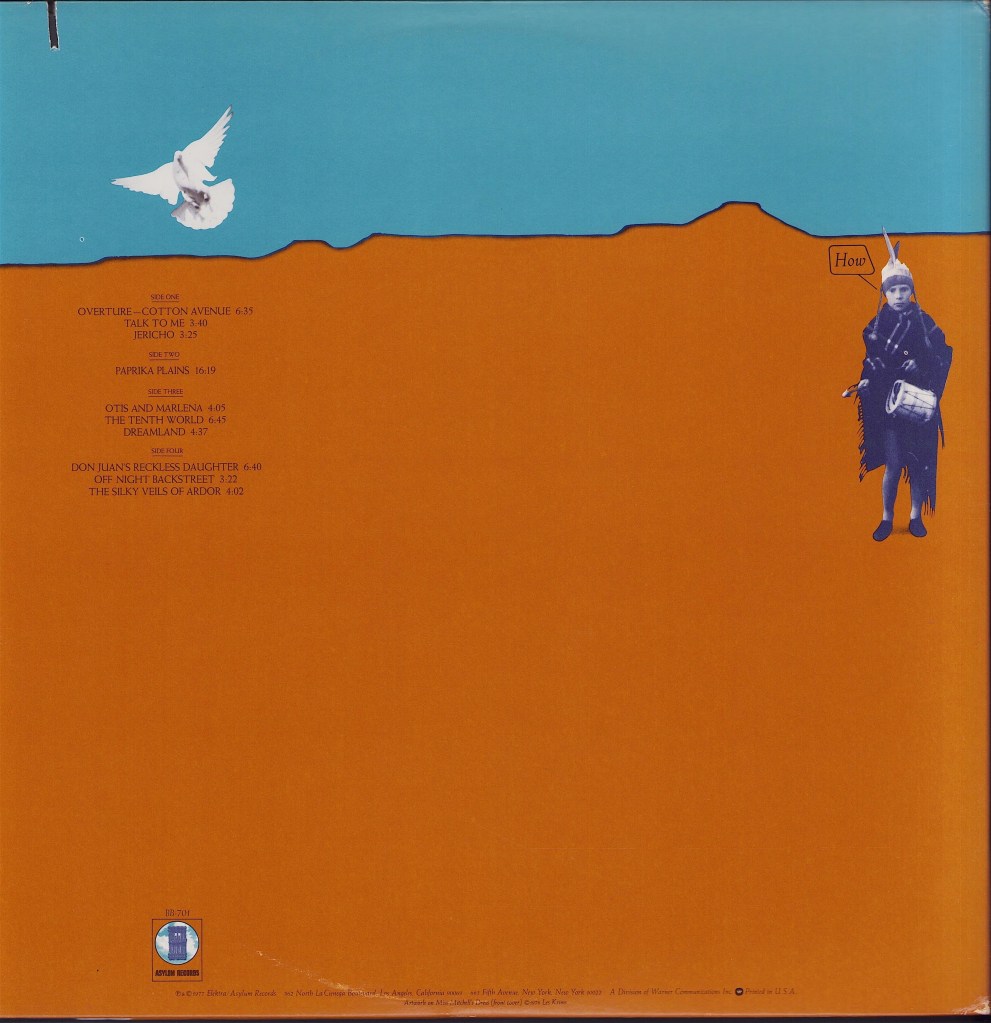

On its release, Kate would jokingly refer to Aerial as a “Great Danes of Love” given its parallel in structure to the earlier Hounds of Love. Whilst the former was essentially one record split into two halves the latter would turn into a complete double album. A problematic often missed here is that the two halves of Hounds of Love have fundamentally little connection yet on Aerial the two records act as linked reflectors of each other – a sea of honey and a sky of honey echoing (and this is again often overlooked) the emotions of the sea and the feelings associated with the air and sky respectively. The first is altogether more driven by grief – itself an emotion experienced as oceanic in its capacity to overwhelm and drown – whilst the latter altogether is more uplifting, in every sense, and life-affirming, and uniting each and the whole is the sense of temporal, of time passing – and of losing a mother and becoming a mother. During the first disc, A Sea of Honey, the feeling of contingency – of the temporary – predominates in a series of meditations upon loss across a variety of forms. The lead single King of the Mountain, a top five hit in the UK, with its reggae and guitar hook riffs is rather misleading indicating something nearer to the pop songs of her yore yet the lyric – a bemused reflection on the spirit of Elvis Presley on one level at least – opens up a concern with what happens after death that dominates all seven songs. Even Bertie, a tribute to her new born son, is set against a Renaissance arrangement that jigs along like a young child playing yet more deeply points towards the universality of mothering as an experience shared across centuries. This sense of domesticity informs Mrs Bartolozzi – an extraordinary piano based ballad that effectively tumbles like its protagonist into a washing machine of memories and grief. Few songs here have drama, let alone commercial appeal, yet this belies both Bush’s bravura and bravery as few, if any, could pull off a chorus of wails of “washing machine” that somehow nearly move one to tears. The other dimension here is of magic – and the great unknown – so Pi reflects on mathematics in song through the incantation-like singing of numbers whilst How To Be Invisible weaves an inverse spell of disappearance over a bass disco riff provided by Mick Karn, the nerd if you like to the celebrity that dominates Joanni an equally mysterious rock elegy to Joan of Arc – or so it seems. The record ends with A Coral Room, a second – yet more complex – piano piece that injects a more personal and direct connection to A Sea of Honey’s overall themes. It is at once a quite beautiful meditation on time passing, given the mixed allegory of a lost world under the sea and the story of the folk song/poem Little Brown Jug, with an exploration of grief at the loss of her mother. As a suite of songs, A Sea of Honey is not immediate but rather imbued with a sense of mystery, space and rumination echoed in often deceptively sparse arrangements. The remastering, if anything, adds even more spatial awareness here. On Aerial’s release, more attention was often paid to the second disc, yet it pays dividends to listen again here and scratch at its layers.

The second record A Sky of Honey still stands as some of the most beautiful music within the popular and contemporary canon let alone Bush’s own legacy. A concept piece, not unlike The Ninth Wave yet here it records the passing of an afternoon into an evening and night and morning again symbolised by bird song (the dawn and evening chorus) that operates – as in reality – in some strange and unexplained symbiosis with the sun and the passage of time. The motivation here is clear and fascinates Bush who then manages to weld this to her own elation at becoming a mother. Bertie figures larger in remastered version than he did before as Rolf Harris is written out and her son is written in, as he did on her 2014 tour, to become the painter and his role in The Architect’s Dream and The Painter’s Link is itself slightly extended. Indeed, the former is lifted from the Before the Dawn recordings. Interestingly, this adds further temporal layers to both the album and to Bertie himself who now exists as both the giggling infant and grown teenager on the same record. The effect of the remastering is perhaps at its most dramatic here for whilst the original suite had a slightly hazy analogue softness the current version has, on occasion, an ear-popping clarity that separates and redraws rather than smudges the arrangements. It’s a moot point as to whether this improves it and ardent fans may well wish to hang onto their originals as well. Thus, it opens with an altogether clearer cooing of “you’re full of beauty” that does undeniably sound like the birds are saying words. Whilst the Prologue nods its head towards the light of Italian Renaissance paintings, Kate’s influences are closer to home – Vaughan Williams to who she directly pays homage in her evocation of the lark ascending. Similarly, it is Delius (previously celebrated on Never for Ever of course) that informs her Song of Summer at intermittent points here, particularly on Sunset. Bush’s own bravura remains in evidence – who else would think to squawk in mimicry of a black bird and pull it off (on Aerial Tal) or write a verb twisting line like “we stand in the Atlantic and we become panoramic” (on Nocturn). As many noted before, the Pink Floyd-esque latter stages of A Sky of Honey are its perhaps its most impressive – or at any rate remind us that she is no stranger to seduction, drama, or indeed laughter – as she giggles uncontrollably alongside husband Danny’s guitar, itself finally unleashed in a near Ibiza club-like celebration of the coming dawn. Aerial is an album best listened with seriousness and attention, and preferably as a whole, to bring out its benefits – it is neither commercial nor immediate yet pays rewards in spades.

Over five years later, Kate would surprise fans with the release of what she called a new album that was in fact more accurately a major reworking of parts of two of her earlier releases – The Sensual World and The Red Shoes – to become her audio version of a Director’s Cut. It is a curious affair and appears sparked at least through finally attaining the rights to “overwrite” her own lyrics to use a passage from Molly Bloom’s stream-of-consciousness that closes James Joyce’s Ulysses. Thus, The Sensual World becomes Flower of the Mountain. Her other main motivation seems to have been a growing dissatisfaction with the digital recording techniques she was using in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Director’s Cut is, perhaps more than anything else, driven by a desire to recreate an analogue sound. Seven tracks from The Red Shoes and four from The Sensual World are given this treatment including very radical re-workings of several fan favourites includes Moments of Pleasure and This Woman’s Work. The former is stripped of its chorus entirely in favour of something approaching a humming interlude whilst the latter is slowed down and stretched out in space to become something nearer to an elegiac if not existential reflection on chances lost. These two long tracks form the core of an album which, by and large, injects intimacy and reflection where once there was studio invention. Moreover, there appears to be something of a desire to re-write her treatise on love from the vantage point of middle age, and perhaps marriage, rather than youth. It’s a moot point, though, whether this really improvesthings. Whilst the Trio Bulgarka flooded The Sensual World album with a kind of Eastern delight here they are kept to the side-lines in order to observe more closely the rest of the songs of which they became such a part. Flower of the Mountain in its analogue fug and bass rhythm heavy form has little of the sensuality of the original and This Woman’s Work, whilst admirable and altogether more raw, is arguably no better than what was already a very fine song. Worse still, Deeper Understanding uses Bertie’s vocoder-ed voice to laughable effect where once the Trio Bulgarka brought the computer to life, although the Gabriel-esqe rhythm section at the end does lend it something. The only true saving grace from The Sensual World here is the altogether sparser version of Never Be Mine which sees husband Danny’s guitar providing the emotional edge and adding to the growing sense of nostalgia that figures large on the record. Tracks from The Red Shoes fare rather better – Lily gets a more rhythm-based feel combined with a ballsier vocal to sound more like a lead single it should have been whilst The Song of Solomon sounds more direct and altogether more adult. That said, nothing much changes on some of the other tracks besides, for example, a lyric swap of “sweet” for “sad” on And So Is Love – it seems at least Kate herself is happier now. Which leaves what can only be called the “doing an impression of Mick Jagger stoned in the bath version” of Rubberband Girl to close the album. The harmonica is new and when interviewed she explained she put it on the end for “fun” yet one is left with the feeling that, in the act of clearing out her closets, Director’s Cut is the curate’s egg of her collection and remains the album which Kate needed to make for herself rather than anyone else.

The surprises of 2011 were not over for, later that year, she released an album of new material for winter entitled 50 Words for Snow. What stood, and still stands, out here more than anything else is her return to more piano driven song writing. Taking its cue from the likes of Mrs Bartolozzi this is predominantly a record of two defined, yet nonetheless pretty sparse, halves. The first comprises a suite of long, classically inflected songs culminating in the near fourteen-minute reverie of Misty, an astonishingly sexualised tale of a tryst with a snowman. Prior to this Snowflake evokes the hush of the first fall of heavy snow via a duet with her son who is neither the infant nor the teenager as before on Aerial but the pre-pubertal here. Bertie’s voice is chorister boy high but caught, consciously, before it breaks. Thus, it is not only an ode to the magic and strangeness of snow but a deeply affecting homage to her son’s, and indeed all men that were once boys’, voices. The more straightforward of the trinity is Lake Tahoe, evocative of freezing cold and Victorian ghost stories, telling the tale of a long since departed woman and her dog. The three songs together form a remarkable demonstration of Bush’s skill in evoking atmosphere and mystery as well as the extent to which she has moved away from the three-minute pop song in favour of something altogether more classical in style. The gears shift to up the pace for the second half starting with Wild Man – also abridged into seven-inch single format – at once an evocation of a humdinger of a snow storm in the mountains and a tribute to the yeti or myth of the abominable snowman, call him what you will, in the Himalayas. Bush’s changes in singing are signalled here – and elsewhere – as her voice drops into a lower, and altogether more hushed, register making her forays towards the chandeliers even more astounding on the likes of Misty and Among Angels. The latter was performed live a few years later and the power of her voice now has to be heard to be fully believed – as she might say herself, she has finally found some balls in it – and sounds, quite simply, magnificent. Whilst the key of it was lowered for large parts of Director’s Cut, and her theme song Lyra for 2007 film The Golden Compass, dropped a large hint at what was happening, it is here that that her new voice truly comes into its own. What also marks out this album is both its wintry complementarity to Aerial which, for all its references to grief, is a record full of summer and sunshine and, likewise, its embeddedness in observations of nature – snow and winter are evoked in a variety of forms from the silence they create (Snowflake) to blizzards and sense of hazard (Snowed In At Wheeler Street) and from the transformative (Misty) to the downright glassy and mystical (Among Angels). It’s all flagrantly uncommercial and teeters on sheer “anti-pop” in its long, drawn out and intensely – some would say overly – measured pacing yet remains true to Kate’s strengths in invoking mystery from ghosts and yetis to guardian angels.

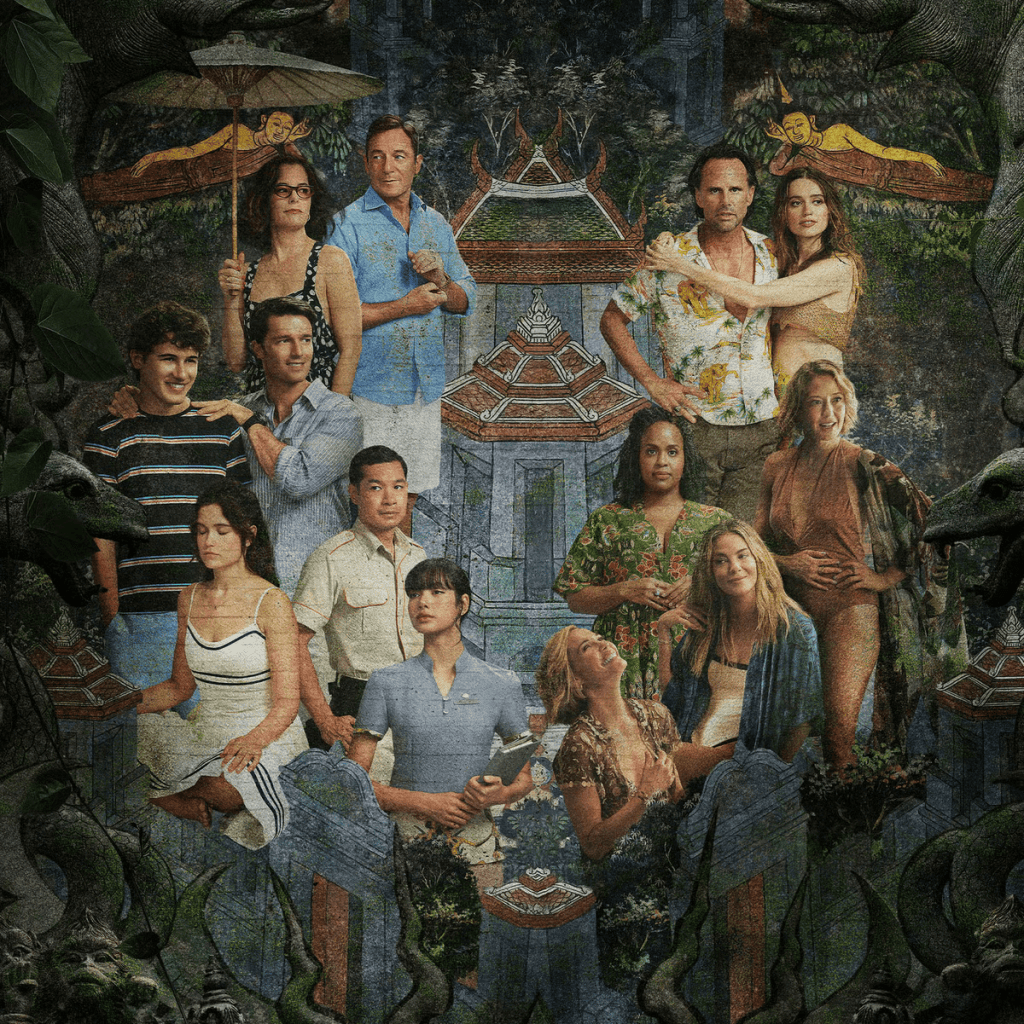

Her Before The Dawn shows of 2014 that took place solely in Hammersmith, London stand as one of the most major surprises of her career and, moreover, recent music history in its entirety. Quite literally, no one saw them coming, quietly expecting another long wait for another long player. Nor were the long shows a reprisal of her earlier career, rather a theatrical and cinematic reworking of her two concept pieces The Ninth Wave and a Sky Of Honey. Eighteen months in the making and, as with the Tour Of Life thirty five years earlier, the effects were overwhelming – a combination of video backdrops, live playing, singing and a theatrical acting out of song story lines that one struggled to take in during one viewing. There was little dancing, yet she sounded amazing. Reviewers and audiences alike were enraptured and in awe, tickets sold out in minutes, and phones were turned off in reverence. As yet at least, no visual record exists, rather a live album attributed to the “KT Fellowship” in honour of those involved and to leave it to the audience’s imagination. Or so she said. More understandably, it’s also not been remastered.

As fans have noted, remastered part four or “the non-album tracks revisited” is not exhaustive. The list is, to say the least, selective. Whilst everything here is brushed up and shiny like new coins, what is more interesting is the juggling of the order which is not chronological rather centred on genre and typology. Particularly savagely, none of The Red Shoes remixes makes the cut at all, though they were not particularly successful either commercially or critically. In fact, only five of the remixes are here – namely those from the Hounds of Love era and Experiment IV. Of these, the Cloudbusting Organon remix fares the best, now sounding like the marching band it was probably intended to; whilst The Big Sky Meteorological Mix has always whipped up a bit of a thunderstorm. Whether the viola driven reworking of Hounds of Love is an improvement is a matter of taste and Running Up That Hill still sounds like it always did – an attempt at turning it into an 80s disco hit. Particularly irritating is the lack of the Army Dreamers single version and there are a mere twenty of her B-sides here. Whilst some such as the bizarre Ken (Livingstone) are perhaps best left behind, other gems like the early piano based balled The Empty Bullring are sorely missed as is the On Stage EP of early live work that was a sizeable hit. Bizarrely, early takes Ran Tan Waltz and Passing Through Air do make the cut as do other B-sides from the Hounds of Love and The Sensual World eras but not the perfectly decent Not This Time (flipside of The Big Sky). Why these selections have been made is anyone’s guess and the omissions are, for any ardent fan at least, glaring. There is of course one new song – or rather the release of a very old one – namely Humming from the pre-Kick Inside sessions where she sounds very young indeed. The standard is generally high, particularly when writing in simpler story telling mode of which Under The Ivy and Walk Straight Down The Middle (complete with peacock shriek) are particularly outstanding. Keen listeners will also note that we get the extended video version of Experiment IV too (though not the same for Cloudbusting). The seasonal hit of December Will Be Magic Again is here though the more percussive mix used on the B-side of Moments of Pleasure would have been preferable. Home For Christmas is best seen as part of the bad decision making that dominated The Red Shoes period and we still get her dodgy French accent on the percussive Ne T’enfuis Pas and unnecessary Un Baiser D’Enfant. Ordering and decision making are also key to understanding the final selection of cover versions. Publishing rights aside, another disc could have been made up of her very fine duets and backing vocal sessions with the likes of Peter Gabriel, Roy Harper, and Midge Ure. There’s a strong Celtic theme to what is here – she is half Irish after all – and this may excuse her ill-advised rendition of Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing complete with ceilidh, a legacy from her Red Shoes era, though the same reggae-meets-Eire combination works well on Elton John’s Rocket Man. It is interesting to note that all her covers are all of work by men not women thus sticking with her tendency to override gender ever since she invoked Peter Pan on Lionheart. It’s a pity Kate has not recorded more acapella as the results are without exception exquisite (My Lagan Love, The Handsome Cabin Boy) which leaves us with her choral reworking of Candle In The Wind. It’s tempting to read something more into her final refrain of “goodbye Norma Jean” that also happens to follow a sensual cover of Donovan’s “swan song” Lord of the Reedy River to close this inclusive, if not exhaustive, collection of her work. She is rather clever after all.

After well over forty years, ten for the most part exceptional solo albums, plus another one or two LPs worth of bits and pieces, a couple of quite remarkable tours and some “yet to be done anything with” video work one can but hope that this is not the final chapter. Yet final chapter it may possibly be. With no sniff of any new music since 2011, it’s easy to feel “Kate Bush remastered 2018” is to, put it politely, the definitive stamp on her career. A book of lyrics entitled How To Be Invisible (ever the joker) and introduced by David Mitchell adds to this sense of someone wrapping up. Her decisions of recent years have, however, emphatically proved that she is the mistress of surprises. As ever, we wait.