The recent success of Kate Bush’s ‘Running Up That Hill’ due to its incorporation in the hit Netflix show Stranger Things, returning to top the charts 37 years after it was first released, perhaps illustrates rather more than a resurgence of interest in a great song. The song was originally a major, if not monster, hit for Bush in 1985 as the lead single from her “soon-to-become-a-classic” album Hounds of Love. At that time, you heard it on the radio or saw the video (Kate and Michael Hervieu dancing, dressed in Japanese hakamas and directed by David Garfath with vertiginous camera work) and, if you liked it, you had to trot off to your local record shop and buy a 7- or 12-inch vinyl pressing of the song. The 12-inch incorporated an extended version as well as the piano based b-side “Under The Ivy”. Despite becoming a million seller in the UK alone and charting worldwide at number one for multiple weeks in 2022, it was never re-released. You’ll also have a tough job getting a vinyl or any other hard copy of it barring buying the Hounds of Love album on vinyl or CD, remastered or otherwise, or ordering the vinyl compilation that accompanies the show*. Its current success is entirely due to its digitisation – downloads and streaming. Indeed, when Kate Bush re-recorded it and indeed re-mixed it for the closing ceremony of the 2012 Olympic games you could only get it on download then, and it went top ten all over again.

My point is that within 40, let alone 50, years the consumption of music, and popular music in particular, has been transformed. And this is not just a matter of formats. Like many aged over fifty, I was introduced to music via a mix of my parents’ vinyl record collection (my mother was a fan of the folk music of the 1960s and 1970s as well as obsessed with Neil Diamond), the radio (BBC Radio One was known to play the chart topping hits), and the TV – Top of the Pops particularly was a staple on Thursday evenings giving a run-down of the top 20 or later top 40. Artists would perform live in the rather tiny studio or, as time went on, videos for their hits were shown. Vinyl had its appeal, those lovely big arty covers and often lyrics to read, but also its drawbacks. It wore out, got grimy and scratchy and if only a single or the like you were perpetually turning the thing over to play the other side. The record players themselves developed in sophistication from cranky all-in-one boxes created to look like furniture to stereo systems of separates housed in much bigger boxes. But the almighty problem of portability remained. Hence, when cassettes and, more to the point, portable cassette recorders and players came in during the 1970s, one spent endless hours compiling copies and playlists to use elsewhere. Whilst headphone sockets were common, the private listening experience did not fully take off until the invention of the Sony Walkman in 1979 that would then dominate the music consumption of an entire generation as youth stuck ear buds in their ears or headphones on their heads to listen to their favourites everywhere they went. Cassette tapes had an annoying hiss, however, and were liable to stretch and break. Reducing this via Dolby helped but then you lost the upper treble range as well.

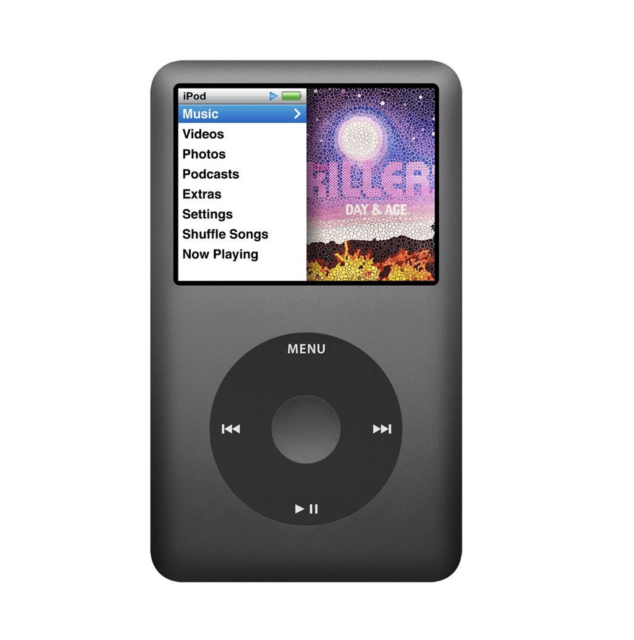

Yet these shifts were minor compared to the one that was to come only a few years later with the rise of the compact disc or CD. This offered portability, near indestructability, clear – if sometimes rather harsh – sound, and the ability to skip/programme and generally jiggle the tracks. The packaging was a tad tacky – a lot of plastic and squinty pictures yet CDs disguised a more dramatic development – digitisation. Although many were recorded from the original analogue studio tapes, they would increasingly be based directly on studio recordings that became digitised themselves. The technology of the studio itself was gaining apace and this was, on top of all else, the era of electronic music was now moving on from the pioneering influence of Kraftwerk to the disco-pop of Madonna. This would appear to then set up parallel longevity to vinyl that, despite its limits, had persisted since the pre-war era. Yet, not so, as once digitised recordings the became free-floating. With the rise of the high speed access to the internet en masse in the 21st century and the replacement of Sony’s Walkman by Apple’s iPod the music consumer was then enabled one to download literally thousands of songs or entire albums onto one tiny music playing device. Convenience ruled – you could carry all your music literally anywhere from home to office and from train to gym.

The unknown consequences were indeed less known – the so-called compression or loudness wars would take over as audiophiles complained that the music was quite literally audio-dynamically flattened into one loud note that had neither range from treble to bass nor spatial sound stage as everything just boomed from the middle due to the literal shrinking of file size and musical information. Radios, smart speakers, and much commercial music recording itself can often play into this shrinking the range, so it is, quite simply, louder. The mechanics of listening to music here shifted significantly. The clumsy boxes – whether wooden or metal – that dominated living rooms from the mid-twentieth century became compacted into mini “hi fi” systems, and later smart speakers. The days of rummaging through someone’s album collection to find what they were into are largely gone along with much of the more social aspect of music consumption though this is a complex point to which I will return.

The key shift here was less formats than the development of digital over analogue. Analog worked through recording sounds from the studio as an entire room full of instruments and gizmos onto high quality tape. Indeed, on early CDs and the like you can still hear the hiss of the master tape. Digital music, like computers themselves, created sound that exists as electronic files. Thus, whilst often suitable for chart banging disco, those who liked their complex prog rock and classical complained quality was lost. The solution, temporarily, came in the form of downloading so-called “high resolution lossless” audio files that took up far more computer space yet could outperform even top-quality CD and vinyl pressings in terms of sound quality. They came at a (relative) price however and many a lay listener claimed they could hardly hear the difference. Yet the death of the download does not lie here rather in two other linked developments. First, the commercial problem posed by the ease of copying and sharing digital formats, even “high res” ones; and second, the commercial solution to this posed by streaming even in high quality playback forms. For a monthly fee, as with Sky or Netflix on TV, you could now access tracks by the thousand or even million. Spotify, initially set up as a free entry service in 2006, now offers various tiers of ad free service and exclusives – for a price. Similarly, tech giant Apple got in on the act in 2015 guzzling up the music market of its already iPhone owning consumers. “Hi-res” only specialists such as the US HD Tracks and French Qobuz offer increasingly complex mixes of content that you stream or can, at a price, download and keep. Yet this was supplanted once again as speakers and computer chips in everything from laptops to cars now allowed one not only to play digital content but rather, with now vastly and speedily increased internet connection, stream it not only on music devices yet rather anything capable of transmitting sound. Music wars these days are not between mods and rockers, rather between the money-spinning commercial music subscription services that provide it. It appears a music consumer’s dream – access to everything (well, almost) for next to nothing (well, not really – even ten bucks (let alone premiums) a month is 120 bucks a year, by the zillion, let alone all that advertising…) – music is dead or maybe long live music. Despite the covid crisis, live music is booming and far more profitable than any format whilst – perhaps – the sheer accessibility of it all is the key to its future longevity.

This potted history is well-known and of no surprise to anyone informed enough or old enough to remember it. What is in question is the way this reshapes the entire consumption of music per se. Prior to this it is perhaps worth making a comparison. For the only matter to parallel popular music’s rapid shifts in its mode of consumption is (ahem) pornography. In 1970 if you wanted pornography, you were, by and large, limited to the top shelf of the newsagent or perhaps a private screening of a movie if you were lucky enough. By the 1980s, video tapes (and with them video camcorders) were nearly as ubiquitous as cassette tapes. A home grown industry grew to both film and then sell films of sexual activity. Given an influx of money circa the immense demand for sexual gratification, studios were born that could then deliver both higher quality recording and offer distribution, for a price. Thus, one could then nip off to the, frankly limited, top shelf of one’s local video store or find the means of purchasing pornographic films via advertising in the back of magazines and then struggle with import restrictions. Video to video copying was rife yet, like vinyl records, was surpassed by the superior and lasting quality of the DVD that like the CD would then dominate until the internet, once again, took over. For producers, popular performers were turned into porn stars and a few directors made names for themselves in the erotic arena, for a time. The limit initially came from illegalities and regulations in trying to physically distribute graphic content internationally. Such content is now commonly digitised and recycled as nostalgia. For pornography, like popular music, is now primarily consumed via websites that offer endless streaming services of some kind. There are a couple of difficulties, however. First, pornography – despite its apparent internet popularity – is not distributed with the same ubiquity as pop music for it is not watched by everyone – let alone the issues of legalities and laws surrounding it. Women now constitute a growth market as the consumers and not just the objects of pornography, yet one should not overestimate the sheer “maleness” of consuming sex as a visual medium of masturbation. Pornography may not be entirely for men by men and about men’s desires, but it is heavily skewed that way. Second, whilst studios can continue to attempt to cash in on the digital world, the advent of high-quality recording facilities even on humble mobile phones, allows everyone – and anyone – to get in on the act. Consequently, homegrown bedroom fodder finds another home on the internet, but it can hardly keep up with sheer tidal wave of titillation offered by an app like snapchat. Yet the process remains remarkably similar to music, driven by markedly related developments in technology that again clearly re-shape consumption.

It is to the question of the re-shaping of consumption to which I now turn. In relation to music, the process has been relatively unilinear. Consumers have become increasingly distanced from a sense of music as a physical commodity and increasingly see it as a floating miasma of sound. The sheer solidity of vinyl, the weight, the covers, and artwork were reduced in the transition to CDs let alone digital downloads and streaming. Interestingly of course, vinyl has seen a resurgence in popularity overtaking CDs as the physical format of choice, yet it is still vastly outstripped by downloads and streaming culture not least due to its expense. The increased popularity of vinyl is also at once a nostalgia trip for those old enough to recollect it the first time and perhaps a form of resistance to the sheer speed and efficacy with which the physical existence of music has come to disappear. What perhaps adds to this is that music is still seen as leisure and recreation and as something separate from computers which, for some at least, remain too associated with work.

More significantly still, our relationship with music has changed. Whilst once the plight of many a parent was to put up with the deafening racket from a teenage bedroom it is now far more common for music consumption to take place privately via ear plugs and headphones. Even linking computers to speakers, amplifiers and other paraphernalia rarely replicates the physical intrusion of the full-on music system or the infamous ghetto blaster. Many a home now does not own much more than the odd speaker; systems are for enthusiasts only. More painfully, TOTP is now reduced to some reminiscence event at Christmas. The sense of communality, at this level, is then lost yet is perhaps reproduced in more virtual terms through the online world of sharing. Somehow even then there is a sense of the creeping death of the social were it not for the resurgence of touring and playing live. Companies have successfully commodified much of this with “buy the album and get pre-sale access to tickets”, let alone merchandise and social media promotion, yet the consumer it seems yearns – and pays – for sheer experience of the pub or the stadium whilst televising festivals has only fuelled a greater interest in going. The music mega-event as in the Superbowl or Glastonbury is now where it, or at least the money, is at. Spectacle. There is a curious contradiction going on here then as the consumption of music slithers from isolated worlds of naval gazing with earphones to the collective euphoria of the live event that, whilst cruelly undermined by the response to the covid crisis, simply refuses to lie down.

What does appear near terminal in this process is, in the case of more commercial pop music at least, is the death of the long player. CDs were very long containing anything up to nudging an hour and a quarter of music whereas the humble LP was best suited to forty-five minutes or less (and less still if audiophile remastered and played at 45 rpm). Few had the energy to wade through the length of a CD, and the skip and programme function clearly came in handy. Yet this paved the way far more radically for the relentless hop skip and jumping of streaming turning everything from heavy metal to disco pop into pick and mix – even contemporary popular classical musicians such as Max Richter and Ludovico Einaudi need singles – digital ones as the hard copy of the “45” is long since as good as dead. Interestingly, the vinyl revival challenges this too as few buy an LP – particularly given the prices – for a track or two. Well, sort of, as the appeal, sadly, lies less in loving the sense of story a record offers than in the immense marketing of the packaging from pictures and posters to the endless “limited edition” snazzy colours, patterns, decoration and even liquid filling of those circular pieces of wax plastic. Part of Taylor Swift’s marketing, for example, involves the endless permutations around which her music gets sold with different colours, photos, the one extra track, and so on – thus her dedicated fans tend to end up spending fortunes on acquiring every variation. Consequently, listeners are increasingly less “sold’ on stories – that sense of narrative that forty-five minutes of music might create – and more on product. The significant number of those who buy these snazzy packaged albums more as objects of worship than as anything they actually listen to, in that many are not even in possession of a turntable, plays into this. Part of this depends on the so transparent you miss it factor that music is now sold increasingly multiple formats – the vinyl’s (plural), streaming (subscriptions), downloads (deluxe and non-deluxe versions, lossy and lossless), CDs with variant packets, cassettes in differing colours and so on. It smacks, somewhat, of children and candy stores, yet more to the point the most fundamental principle of all marketing – diversification.

Given the (il)legalities, pornography was less concerned with commodities rather with access. The internet has given it this in immeasurable spades and, despite the moves of Islamists, dictators, and some parental campaigns, it remains utterly uncontrollable. Whilst pornography was never particularly shared as a communal experience beyond the private worlds of couples or swingers it’s now become Alice’s dystopian wonderland of a rabbit hole that individuals go down. The endless, seamless, searching for kicks is like cake, the second one never tastes as good as the first – it needs to go further, harder, dirtier, raunchier, more extreme. Or just plain weird. The world of exhibitionism and voyeurism becomes limitless – furby anyone? Look it up. The comparison with the desperate attempt access porn, even as late as the 1990s via the top shelf, your mate’s or your mate’s dad’s collections of mags and movies could not be starker. Whether this truly causes a world of addiction and unrealistic expectation, let alone violence, is – frankly – too soon to know though the sheer tidal plethora of the stuff has to be impacting something. What is known is that it opens the door to the amateur creator. Whilst phones have long served as a useful way to listen to digital music on the go, the relentless advancement of photo and video technology to outstrip, or at least keep up with, most semi-professional photographic equipment has turned near everyone into a potential porn star and sex – virtual now as well as real – as a prime gig economy of the twenty first century. Rather than music paralleling pornography, the world of porn increasingly apes music – anyone can do it, but can they sell it? There is some sort of market it seems for anyone from 9 to 90, from kink to kinkier, and from utter vanilla to endless fetish.

The parallel with music also returns then not only at the level of production, rather exploitation. Not just viewer or viewee, rather the streaming platform provider that pays a pittance whether its music or sex. There is also something else similar here as whether music or erotica the process of consuming via the internet is equally isolating and without control. Consequently, parents panic as the deafening racket from the bedroom or the magazines under the bed are replaced by, well what? Who knows. Enter attempts to placate parental anxiety and exert control via nanny the state – a series of frankly idiotic laws that do little than just make it harder to produce non “main/male-stream” porn, the opt in not out on adult internet provision that even a child of ten knows how to get around, and those utterly pointless “parental advisory” labels on CDs. It’s all a rather sorry “state” of affairs.

There is of course a further parallel as music itself is increasingly sold not as sound in any way yet rather as image – from Tiktok clips to the full-on pop video or concert broadcast – what was once merely visually sold through the picture on the cover or the gyrations on a live stage is now an entire visual arena in itself. It is hardly surprising then that the pop video comes near the top of the list in examples of the “pornification” of popular culture and sexualisation. The concern most often raised here is in relation to consumption or rather the impact of all this gawping, particularly upon the young. The attempts to control at source whilst easily supplanted also miss the issue of who selects what that someone else can see.

Underpinning this is the problem of ownership in both cases. Both music artists and sexual film makers require equipment and distribution if they are to become more than a minority home produced item. Whilst recording one’s guitar twanging on a computer or sexual activity in the bedroom via a mobile phone is now more possible than ever for it to profit requires both far more investment and some kind of online platform. So, performers – whether musical or sexual – struggle to retain or even gain ownership over their own output. Recent protests and attempted boycotts by a number of well-known recording artists over the pittances paid by online music streaming platforms would appear to echo well-known histories in the battle for artistic control. From Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley to George Michael and Michael Jackson, there remains an on-going litany of music-related disputes that – given digital copying – increasingly centre on plagiarism hence the recent losses of Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke for the song “Blurred Lines” that was, interestingly, itself also accused of inciting sexual violence in a way similar to pornography. Such cases are less well known with pornography itself given the morally ambiguous and often anonymous status of the sexual performer – though there are a few infamous and historic cases and historic of models speaking out – yet the potential for exploitation in the world of online performing is vast. In economic terms, there is ample opportunity yet also vast threat.

There are shifts here also in terms of the power relationships of consumption. Pop music has a history of fickleness, yet some artists and groups become “household names” that most, if not all, at least know and in some cases follow and like. Consequently, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Abba, and many big names of the 1980s from Madonna to George Michael were beloved by billions both younger and older whilst major scandal could not rock Michael Jackson’s following. Yet one struggles these days to draw parallels. Adele appears semi-retired whilst Ed Sheeran is simply too middle of the road. The world’s largest contemporary seller by a country mile is Taylor Swift yet few can name many, or any, of her songs. Swift is illustrative of something far wider, namely the power of social media and the internet plus a frankly terrifying juggernaut of marketing that sees fans queueing for hours to purchase music they already have in another format, with a different cover, or colour, or something. What is lost in all of this, despite the popularity of live shows, is the collective or communal sense in which music means something when it is endlessly pumped through computers and phones to individuals – radio let alone TV is in fragmentation freefall where only the “mega event” of the likes of Glastonbury can engage many on and offline, on and off media. Underpinning all of this are shifts not only in technology yet rather the increasing domination of capitalism. Even well-known stars complain of the lack of money for them in music, the eye watering exploitation of streaming and the immense costs of studios and tours alike. Yet the ecological critique of the carbon footprint, far from removed by streaming but undermined more by the download and keep model, means that some such as Massive Attack are unlikely to ever tour – or perhaps record – again. The internet appears to disseminate and certainly facilitates sharing yet “indie” artists such as Wolf Alice, amongst many others, have felt themselves forced to feed the conglomerations to expand their own reach and not collapse. Others meantime have sought the rights to their own material yet it requires wealth to achieve.

All in all, there’s something just a teensy bit gloomy in all this. Even sad. That the excitement of hurling off to the record shop, even queuing for hours, or that stomach swirling excitement of the first foray into dirty pictures that still left far more to the imagination is just plain lost in a sea of over-mediated, over-commodified, blasé gorge festing on new tunes, new videos, new – well, somehow none of it ever quite is. The resistance to this comes in the form of indie record stores and “record store day” where music is only – initially that – is released in a physical format you have to visit a shop to get yet this in itself is becoming an increasingly profit driven racket of re-issues and the gig economy of ebay. Still, you do at least have long chats with other like minds whilst waiting in the queue.

So, running up what hill where? I am truly delighted that millions have listened to Kate Bush who had never heard of her before let alone see her twirl on the telly, yet somehow still feel they’ll all just end up somewhere else, lost in the sea of it all, not apoplectic with excitement when she releases another years later that you cannot wait for, then play to death, then fondly remember for ever more… Bush herself is an interesting case in point. Famously “reclusive” her career has been dominated by her desire to gain control of her output. She was doing that way before Swift had even heard of it. Such was the adversity of her reaction to her early “pornographic” typecasting and promotion, since the 1980s she mostly only allows her family photograph her and owns her studio, her record label along and near all rights to her output. Yet such a reluctance to “play the game” would now stop her ahead of starting had she not achieved the successes she did. There’s a twist here, though, as her recent success has little to do with her music at all yet rather the media itself that spins unknown futures of its own – namely a hit show on TV. So, perhaps, it is more apt to end on another tune, Talking Heads, ‘Road to Nowhere’, that actually came out the same year as ‘Running Up That Hill’…

*it was eventually re-released on CD single format, but in the US only