In late 1977, I was fourteen years old and still viewed Joni Mitchell through the lens of my mother who – like millions of others – extolled the virtues of her album Blue and her wider early “folk” period. In 1978, I would plunge headlong into a love of her music – all of it – and extol myself the virtues of her much vaulted “mid – period” where, in another hopeless appropriation of a category, many accused her of getting “too jazzy”. Mitchell’s music in many ways defies all categories, past and present, yet appropriation is a theme that now once again seems to stick. The case in question is the re-release and remastering (cue my excitement) of her so-called “mid – period” that started with a boxset containing Court & Spark and The Hissing of Summer Lawns, two of her most applauded albums (at least now – the latter was much maligned at the time) sounding stunning at the hands of Bernie Grundman. And now a second boxset including what is widely regarded as perhaps her last true masterpiece, Hejira, plus Mingus, the live set Shadows & Light, and indeed Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter itself originally released late in 1977. The records are to be released in boxset form in multiple formats and in the exact same presentation as before bar one, namely Don Juan. On looking at the promotional materials I was surprised to realise that the cover for this record is now unrecognisable in comparison with its predecessor. Whilst I had heard the odd rumbling, I remained bewildered quite as to why. The answer centres on appropriation, cultural appropriation that is, of racialised imagery.

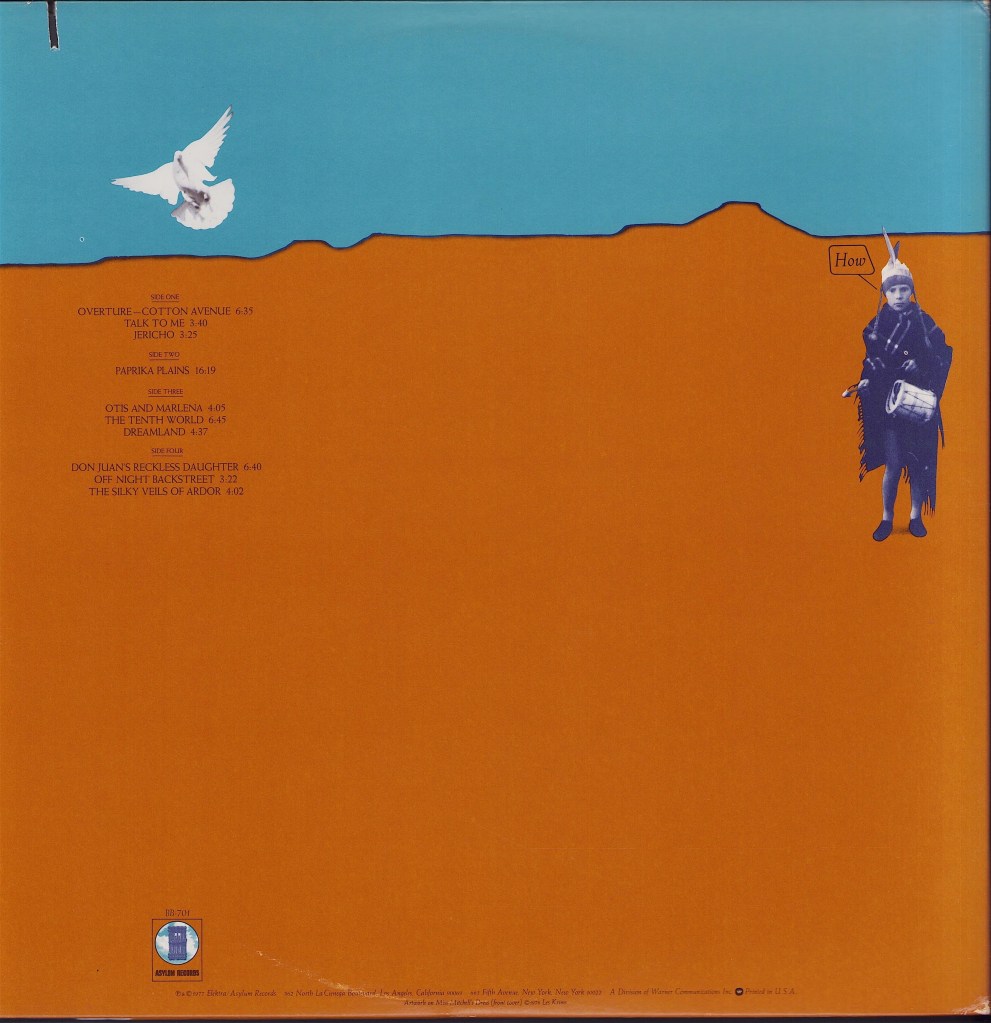

The original album front cover displays – amongst other things – the image of a black male pimp dressed in hat, shades, and fancy clothes and donning a thick moustache. The man appears to dance with Joni herself pictured in a top hat and wearing a dress painted with imagery involving a female nude, birds, and odd balloons that echo the art of Jeff Koons. The figure also dons what seems to be a medal with which he perhaps charms the birds from the trees. It also pictures a mysterious boy dressed in something akin to a prom suit with plimsolls, standing sideways on, and – on the rear – for the cover is gatefold, a small picture of what at first seems to be a boy but on closer inspection appears to be a childlike version of Mitchell herself dressed as an American Indian saying “How”. The title of the record is also in a spoken bubble from the pimp whilst the entire cover’s background is a deep burnt orange offset by a bright blue strip at the top – a clear reference to the Paprika Plains of track four. So, on the face of it, we have Mitchell playing with racialised imagery echoing the music itself that draws on African themes, among many other things, and which incorporates a string of black musicians including Wayne Shorter and Chaka Khan plus Don Alias, the percussionist, whom she was also dating at the time. So far so good – until one realises (when informed) that the pimp character is in fact Mitchell herself in blackface.

Concerns were raised, then and now, that the, then and now also, “goddess of white folk music” Joni Mitchell was acting in a way that was racist. Mitchell’s accounts and practice of her persona later called Art Nouveau did not end here but rather started with her donning the guise for a Hallowe’en party held by bassist Leland Sklar in 1976 where – literally – no one guessed her real identity; and the imagery would later appear, briefly, on tour in her homage to the musicians of Beale Street, Tennessee on the song Furry Sings the Blues. Mitchell’s discussions of the incident are scant – if candid – including an encounter on Hollywood Boulevard where a similarly dressed black man complimented her style and an interview with the LA Times where she stated she felt herself akin to “black” in her poetry and musicianship and closer in kind to Miles Davis than white folk artists. One interpretation then is that Art Nouveau, and Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, are part of a conscious resistance to, and statement of separation from, the media induced folk tag she had had hanging round her neck since the 1960s.

Yet over 45 years later this fails to convince. From the point of view of cultural appropriation, Mitchell is seriously naïve if not downright racist in her adoption of the imagery whilst her defendants rather glibly cite her celebration of black musicianship culminating in the late Charles Mingus asking her to collaborate with him on what was to become her next album Mingus. This album was, arguably at least, readable more straightforwardly as a direct tribute to the jazz legend. Indeed, it is necessary to spell out the difficulties invoked through the Don Juan cover rather more clearly here. The assumption made under the term “cultural appropriation” is that the powerful (here the wealthy and white Mitchell) exploit the creative productivity of the oppressed (here the characterisation of the black male pimp) or, at the very least, neglect consideration of its history (here the legacy of rape and ownership, slavery and sexualisation, that dominates much of the United States cultural history in particular and informs the character of the pimp). In sum, it appears to play with and trivialise that which is far more serious; and, to which attached, there is an immense suffering that still requires recognition and redress. Interestingly, similar statements are often made in relation to gender where so-called “TERF” or trans exclusionary radical feminists argue biological males, including wannabe female males, trivialise and misrecognise the historic and cultural embeddedness of the oppression of women in attempting to dress as them or indeed become the same as them through surgery.

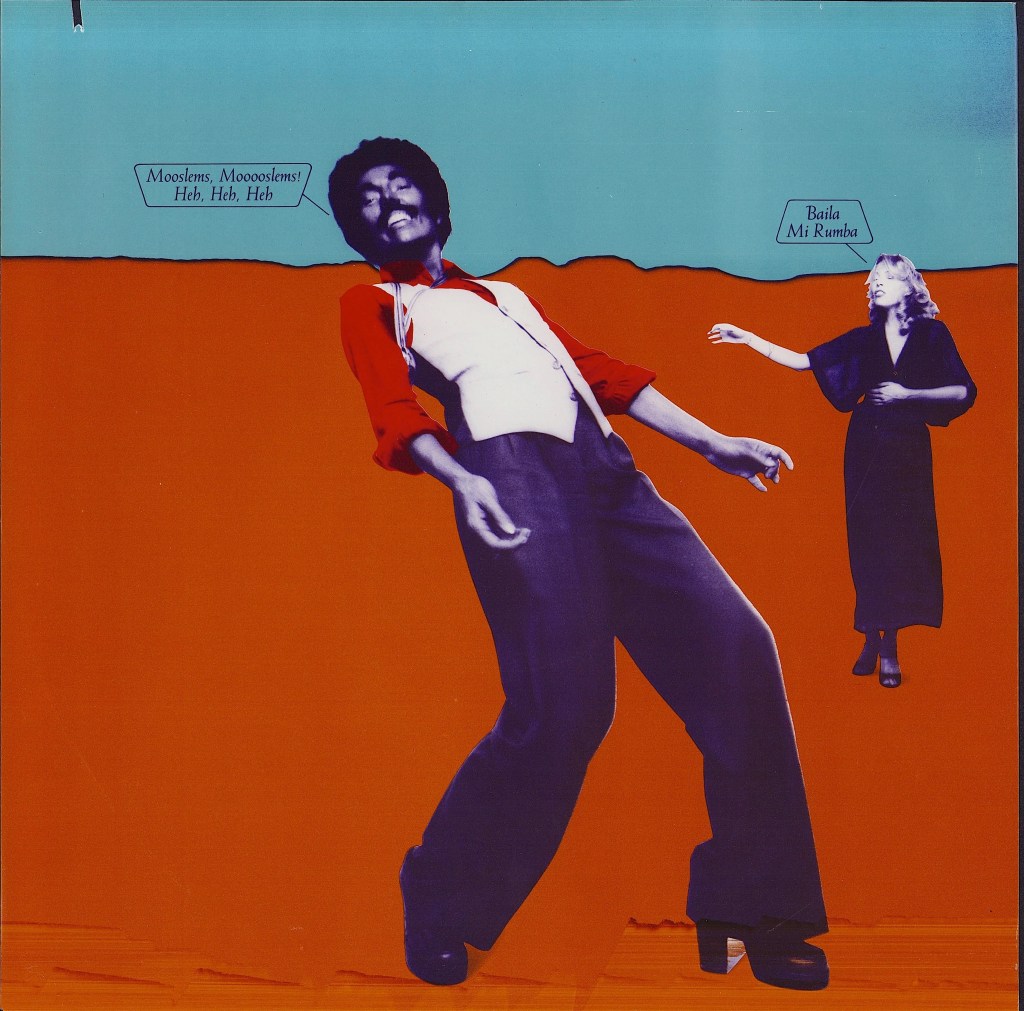

However, neither of these rather simplistic approaches is sufficient to understand the complexities of a cultural text. Cultural texts may refer to any manner of things from advertisements and imagery to magazines, works of art, TV programmes and films, or indeed music and album covers. Moreover, returning to the artwork for Mitchell’s Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter we in fact have a double album housed in a gatefold sleeve that has a front, a back, a foldout interior, and two semi-illustrated inners that contain the records. This opens, simultaneously, a diversity of imagery for scrutiny and further food for thought on the theme of racism and appropriation. Of more direct concern is the imagery that houses the discs. One shows Joni, in the same or similar dress, yet without the montage of assorted imagery shown on the front cover, dancing with another version of her persona Art Nouveau without the jacket or hat yet sporting an afro. The figure here is more of a giveaway as Mitchell’s slim wrists and distinctive long fingers are on display. More to the point Mitchell’s character calls out “Baila Mi Rumba” (Spanish, dance my rumba) to her Art Nouveau persona who responds “Mooslems! Mooooslems! Heh heh heh”. Whilst playful, the language at least is scrambled and potentially derogatory. Yet more confusingly on the other inner we have a further picture of Mitchell in the same dress yet shown from the rear calling out to a “Koons” balloon “In My Dweams We Fwy”. This is clearly a play on the line “in my dreams we fly” from the album’s closer, The Silky Veils of Ardour, a melancholic lament on the power and pains of love. The doves that otherwise litter the record cover are also referenced here in the “crazy beating” of her heart and the desire to take the wings of “Noah’s little white dove” to “reach the one I love”. However, the phonetic mispronunciation speaks to something either inchoate or childlike. Or, more insidiously, the accent of someone “foreign”. Interpreting this miscellany of imagery is far from easy. Whilst some of it is a clear reference to various song lyrics other parts such as the child/children and Koons style balloons are far harder to read. Muddying the water still, the racialisation of the imagery is hardly limited to black culture but also involves a parody of American Indian heritage. Children playing games of “cowboys and Indians” are invoked here whilst the word “How” is at once childish or raises the question of “how” indeed any of this might make sense…

Mitchell’s playfulness in all of this is at once perhaps conceived as a simple artistic conceit yet equally raises questions as to how seriously she understood that which she was playing with. It is worth remembering here that cultural appropriation of such imagery was common at the time ranging from long running comedy and minstrel shows, including the BBCs own that finally came to an end in 1978, to the “golliwog” figure that both adorned jam jars made by Robertson’s and became a child’s soft toy, neither of which was dropped fully until the twenty first century. There is clearly a strong sense in which one neither can, nor should, hold Mitchell responsible for something far wider particularly when the main target was fundamentally unrecognisable as her. Similarly, Mitchell’s dabbling in the mixing of musical forms both white and black, or rather more accurately Western and African, in origin foreshadowed acclaimed work by both Paul Simon (Graceland, 1986) and Peter Gabriel (IV or Security, 1982). That both artists have been far less subject to scrutiny here speaks to less controversy concerning their albums’ covers but more to that other thorny issue, namely gender. Returning to Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, again the figuration is inconclusive. Whilst women dressing as men in general is often heralded as brave and subversive – cue the figure of Marlene Dietrich in a tux – crossing racial lines to depict a man who is black here offsets this radicalism almost entirely into something more reactionary. Similarly, the imagery of the pimp has little of the connotation of either butch lesbianism or later drag king culture celebrated by the likes of Jack (nee Judith) Halberstam or k d lang. What rattles more still here is Mitchell’s image of herself as an American Indian of not entirely distinct gender that perhaps “beat the drum like war” on Paprika Plains. One is left with a sense of constant ambiguity in all of this whilst ambiguity itself is key to any understanding of any cultural text as something that has meaning that is polyvalent not singular in one truth. The difficulty of cultural appropriation arguments is that they tend to assume specific truths to interpretations that often do not exist – that one known cultural text a is easily interpretable as b and that this the constitutes truth c.

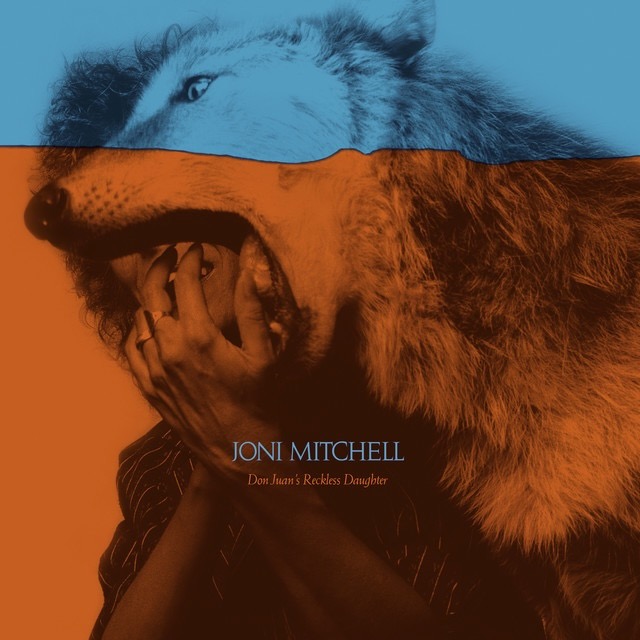

Which rather brings us to the frankly indecipherable imagery that forms its replacement for Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter in 2024. Not all the artwork is available before the album’s release, but we have a clear image of the front cover. Nor is it known whether the cover is single or gatefold or whether it includes decorated inners, but we can safely assume that little of the original imagery persists beyond the orange and blue colouring. Turning to the front cover itself, we have a photograph of Joni mostly obscured by what appears to be a dog or a wolf in whose mouth she has her hand. The immediate difficulty presented, for her fans at least, is that this imagery appears drawn from another era, namely that of Dog Eat Dog, an album released in 1985 that shows a painting by Mitchell of herself with dogs and wearing what seems to be the same pinstriped jacket. The front cover here appears aggressive or even bloody whilst the dogs appear calmer on the rear but there’s has been a car crash, and the overall picture is centred on a road at night. The associations of danger and violence are clear, echoing much of the record’s preoccupation with the nefarious politics of the 1980s including a scathing critique of the Reagan era, tax evasion, evangelicalism, and wider consumerism. What such allusions are doing on a cover for Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is anyone’s guess. It could be said, at a push, that connections are being made between her attack on corporate greed in Dog Eat Dog with the racialised musical expression of Don Juan yet this collapses entirely if you do not recognise where the imagery is coming from. Perhaps more pertinent, is her hand in the mouth of the wolf like dog begetting the expression “biting the hand that feeds”. Again, we tend to draw blanks here as this would fit with a commentary on celebrity and fame where the Mitchell critiques the same system that made her wealthy, themes explored far earlier in albums such as Ladies of the Canyon (1970) and more particularly For the Roses (1972). One should therefore perhaps refrain from further comment until the reissue is released and any statement is given.

Yet the fact remains that the cover has been very significantly changed. Given its ambiguity, its near surrealism of balloons and characterisations of contradictory things, and the reliance of the “it’s racist” argument on recognising Mitchell within it when the majority never did, it is arguable the original should stand. Or at least stand with an addendum of explanation. The words cancel and culture spring to mind here when what is at stake is far from being in black and white in any sense.1

- Images show a paper clip mark that is not part of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter’s album’s imagery but high resolution imagery showing text as well as image was hard to find. ↩︎