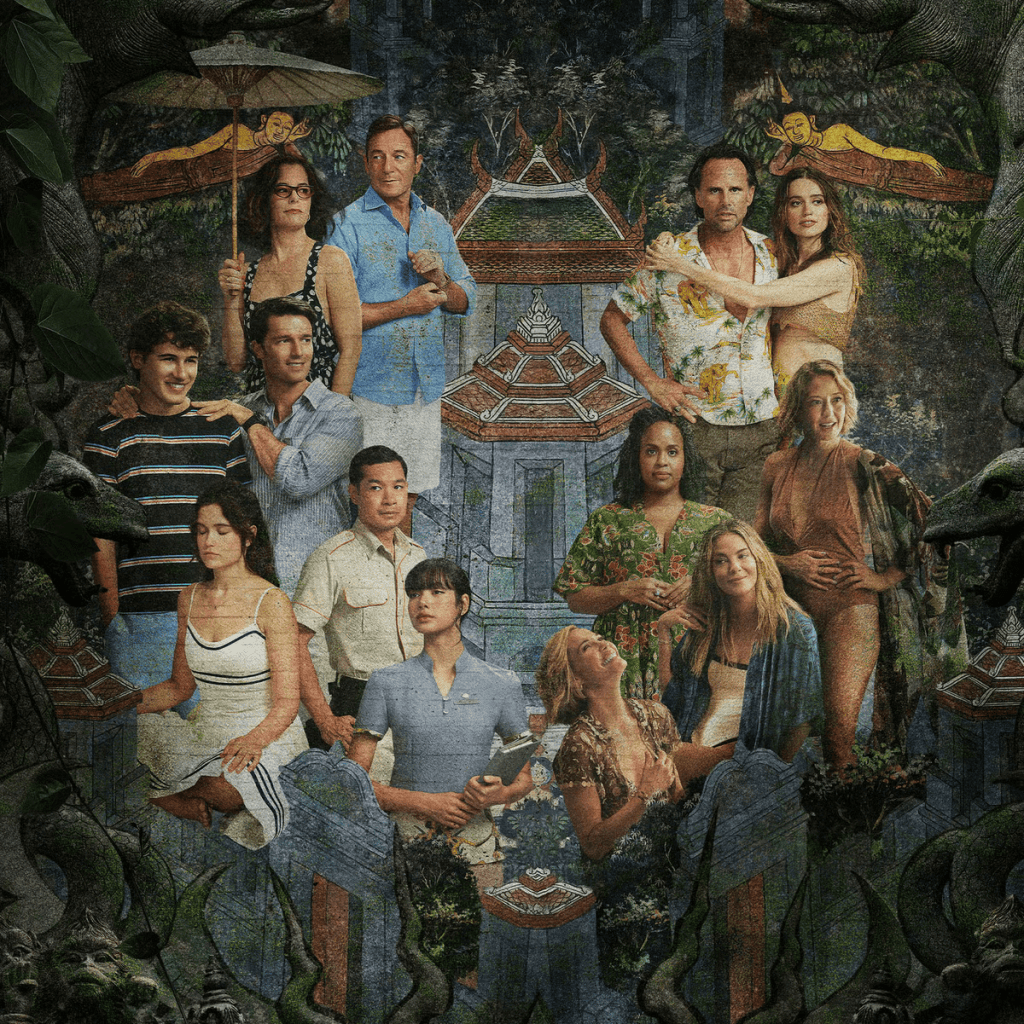

In case you have not noticed, The White Lotus is the multi-Emmy and Golden Globe award winning show launched on HBO (Home Box Office) in the US in 2021. Now into its third season it has lost none of its momentum but rather gained in popularity and influence as a now record-breaking success for the channel, simultaneously broadcast outside of the US via Sky. HBO is well known for its highly successful and influential “adult” dramas invoking much taboo, sexual and violent subject matter such as The Sopranos and Game of Thrones that, if it continues its run, The White Lotus perhaps looks set to eclipse. It is the brainchild of Mike White, also known as a cinematographer, actor and occasional reality TV star, who writes, produces and directs the show in its entirety. The show has received accolades for its writing, acting, and increasingly stratospheric production values and is praised as what one might loosely call its dark satire on particularly, yet not exclusively, North American forms of wealth and privilege. Its title plays upon the mythology of the lotus eaters who laze indulgently in a state of forgetfulness as well as its creator’s name.

It is interesting to question quite why it has had this impact and what, more exactly, sits at the core of its success. I will suggest that this centres not on one rather a number of both thematic and episodic tropes and devices that entice the viewer and tap into wider cultural concerns. These include its plot and narrative constructions; its cinematography; and its drilling of morality and ethical scruples through character driven psychological portrayals that centre most strongly on power and privilege, sex and sexuality, and death.

It is, on one simplistic level, a murder mystery thriller as each series opens with the death of a character (or characters) and then unfolds to eventually show not only who but rather how and why they die from a wider cast of holiday makers staying in luxury hotels. The White Lotus itself refers to a chain of upmarket holiday residences in differing locations that change with each season so the first was set in Hawaii, the second in Sicily, and the third in Thailand. Yet, interestingly, the series also scrambles conventional tropes of the murder mystery genre. We do not know at the outset who has died, or even how many, who perpetrated the crime(s), or why, or even how. It is not a whodunnit nor even a whydunit either rather a mix of all of these and, as some critics have pointed out, it is far too slow paced to work at this level alone. The first series took up six near one-hour episodes, the second seven, and the third eight, the last of which was extended to ninety minutes. In each case, at least half of the episodes are taken up with character building and, in the third, the climax is introduced in the penultimate episode, and then disrupted, only to return in the finale. Thus, we think that Rick’s (Walton Goggins) “monkey is off his back” and Timothy’s (Jason Isaacs) suicidal killing spree is not happening, only to find that they reappear in differing forms with deadly consequences.

This disruptiveness is part of The White Lotus’s appeal; whilst infuriating for some, many more are kept on the edge of their seats. Similarly, multitudes of plotlines are simply dropped or unresolved – how does Shane (Jake Lacy) get away with manslaughter in season one, just what is the connection between Greg/ary (Jon Gries) and a gang of gay hedonists in season two, and what will happen when Timothy’s family find out they’ve lost everything and he will likely end up in prison? Minor story lines are often equally confused – does the truth of the robbery ever come to light in series one for the Mossbacher family beyond Olivia’s (Sydney Sweeney) suspicions, did Harper (Aubrey Plaza) have sex or just a snog with Cameron (Theo James) in season two, and who and what were the gunmen up to in series three as they were not the Russians? These factors annoy some critics intensely and clearly have the potential to throw audiences off-track yet often keep more hooked for the following series.

The show’s most complex plot straddles all series in fact – namely that of Greg’s seduction and, we presume, planned murder of Tanya. She meets him in season one, they are married prior to season two, and in season three – following her death in season two – Greg (now Gary) collides with Belinda who was her masseuse in season one. The fact that Greg (seasons one and two) Gary (season three) has turned up in all three seasons, and Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge) and Belinda (Natasha Rothwell) in two, adds to the sense in which it’s not all over when it seems over. Moreover, the plotline here is extremely convoluted. In season one, it appears Greg is unwell, yet this is never explained and is perhaps a ruse to get Tanya to marry him, whilst in season two he disappears early in the series to go on some kind of business trip but is overheard saying “she doesn’t suspect a thing” on the phone. Tanya is then befriended by the openly gay but decidedly creepy Quentin (Tom Hollander) and his group of friends and cronies. He takes her to the opera to see Madame Butterfly and arranges for her to have a lover for a night in his villa. Her assistant Portia is meanwhile distracted – as part of the more murderous plot – by Jack to separate her from Tanya. Tanya’s discovery of a gun and other paraphernalia on a yacht whilst on their return to the hotel confirms her suspicion that Greg is planning to do away with her as their prenuptial agreement means he will only inherit her fortune if she dies. She then shoots and kills Quentin, as well as his cronies, yet falls to her death accidentally trying to get off the yacht onto a small boat that will take her to the harbour. More obscurely, we are left to presume that Greg will now inherit her fortune and has “got away with it” in parallel to Shane in series one yet, in a further twist in season three, Belinda recognises Greg, now Gary, and becomes suspicious. The now wealthy Greg attempts to silence her with money yet, in a twist that directly replicates season one in reverse, Belinda connives to attain more and rejects both the love and business proposition of her fellow masseur to pursue her fortune alone. Preposterous as much of this is, it perhaps lends a feeling of reality to the fantastical show and its scenery. Life rarely offers easy resolutions, a theme openly and directly expanded upon in the finale of season three, yet fans were left querying this final twist. White appears to have felt the need to ameliorate the outcome that Greg may get away with murder and grants Belinda a cut of his success though, in so doing, her character has to perform a complete moral volte-face and reject a promising relationship. An underlying point, perhaps, is that wealth and privilege will turn even the most innocent. Yet it is perhaps White’s manipulation of the wider mise-en-scène that is key here, a theme I will return to later.

The White Lotus is also a show full of contrasts. Far from being wholly serious, it is often highly, if rather darkly, humorous in places with various characters deployed to primarily comedic effect alongside wider satires on the peccadillos of the rich. For example, the billionairess Tanya, who features in seasons one and two, is neurotic and self-obsessed, in one scene descending into a hysterical breakdown on a yacht that she has hired to scatter her mother’s ashes, much to the horror of her fellow travellers who are otherwise seeking a romantic dinner. Similarly, in season three Victoria (Parker Posey) plays the wealthy yet prejudiced wife of a tycoon adopting an stylised Southern American accent to complain about “boat people” and “Buddhists” (pronounced boo-dist) explaining that the least one can do as someone highly privileged is to show the less fortunate that you enjoy it!

On the flip side, there is also much tragedy and unhappiness that emerges for almost every character. Most major and some minor characters are explored in depth to reveal their hidden miseries and concerns from hotel managers – Armond (Murray Bartlett) in season one is a gay man recovering from drug and drink addictions whilst Valentina (Sabrina Impacciatore) in season two is a repressed lesbian – to their preposterously wealthy guests who worry about everything from testicular cancer to relationship problems and financial ruin. Thus, there is a near relentless scrambling of genre going on where the audience is at once empathising with, yet equally horrified by, the characters presented who induce feelings of both fear and upset as well as ridicule. Whilst most drama shows are keen to present characters who are complex and neither wholly good nor bad such contrasts in the show are often ratcheted up to a degree that is as unsettling as it is involving. So, the audience is encouraged to sympathise with Armond as the pressured manager of oversized egos staying in his hotel whilst at the same time realising his self-destructive behaviours of stealing and drug taking are wrong – and, in relation to defecating in the suitcase, extremely funny – or to recoil in horror as Tanya’s egotistical demands increase yet empathise with her fragility and suffering. This psychological “scrambling” has much to do with the show’s success.

More significantly, plotlines here fling audiences around like a magnetised moral compass. The foursome at the centre of season two, for example, invoke feelings of desire and disgust given their good looks and confused orientations – Cameron is arrogant and vain whereas his best buddy Ethan (Will Sharpe) appears guilt ridden and struggling with some kind of sexual impotence. Underpinning this are themes of sexual jealousy and possessiveness that, even at the end, appear unresolved. Will’s sudden amorousness towards Harper appears to follow a potential fling with Cameron’s wife Daphne (Meghan Fahy). Similarly, even relatively minor characters are complex so that Jack (Leo Woodhall) swings from being a sexy Essex boy to a criminal with a background that alludes to him being groomed on the streets. Similarly, the doe-eyed Mook (Lalisa Manobal) of season three turns out to be pushing her good natured and devoutly Buddhist boyfriend Gaitok (Thame Thapthinthong) towards aggression and killing. It is this onion peeling of character and psychology that is so compelling, akin in kindness to the psychological thrillers of Hitchcock and Lynch yet is here framed within a TV series not film.

White is not averse here to the tricks of the reality TV genre, however, using sex in particular to titillate and draw in his audience. Thus, in season one, Armond is caught cavorting – in fact rimming in full shot – one of his underlings in his office whilst the apparently heterosexual bad boy Woodall is caught buggering his boss Quentin, and all series feature one if not more (prosthetic or not) cocks on show. What increases the amplitude here is that these are not necessarily minor characters or even throwaway plotlines rather Saxon (Patrick Schwarzenegger) in episode one of season three is watched desirously full frontal by his younger brother Lochlan (Sam Nivola) invoking themes that are not just incestuous but homosexual, a storyline that reaches its climax literally and figuratively during a drug-induced three-cum-foursome orgy mid-series, and this is a major part of Saxon’s unravelling. Similarly, Cameron’s shorts dropping in front of Harper is the start of a plotline of “will they, won’t they” that becomes “did they, didn’t they” that dominates series two. White’s own life history seems to play into this as both the son of a father who later came out as homosexual and as someone himself who is openly bi-or homosexual. Perhaps more significantly, given the rise of conservative or even reactionary right-wing politics in the US, these shock style tactics also become jabs at the wider sexual hypocrisy that dominate parts at least of US culture.

As has already been stated, the series is primarily – if not exclusively – character driven. There are interesting gender differences here, however. Characters in any show are presented in three ways – first, through their appearance and dress; second through their actions and speech; and third, less directly through their interiority, silence, and expression. For the most part, yet not totally, greater interiority is given to male characters – particularly in the more interior-focused season three – Timothy’s pain and suffering is a repeated trope shown on all levels including his recurrently horrified facial expressions. This is a pattern repeated in his son Saxon who – in an ingenious piece of casting and playing by Patrick “son of terminator Arnie” Schwarzenegger – shifts from cocksure confidence to confusion and self-doubt. By the same token, Gaitok is repeatedly presented through his “willing to please” smile that covers a multitude of internal terrors; whilst Rick is fully fleshed through his often-dishevelled appearance, perplexed expressions, and highly risk-taking actions.

By contrast, White has something of a fixation with making “rich bitches” the butt of his jokes. This starts with the affectations and posing of both mother Nicole (Connie Britton) and daughter Olivia in season one and culminates in the figures of both Tanya in season two and Victoria in season three who become, in differing ways, resounding sources of humour whether for their childish howling (Tanya) or camp sneering (Victoria). In fact, this sets up one of the difficulties of season three, namely that the three-character study of femaleness and friendship, only really comes together through Laurie’s (Carrie Coon) “at the table” speech (a near Emmy winning moment) in the final episode precisely due to this lack of interiority – the three of them are simply too indistinct. In addition, White might be accused of setting up misogynistic stereotypes but his portrayals of both hotel manager Valentina and good time girls Lucia (Simona Tabasco) and Mia (Beatrice Grannò) as well as the suffering Portia (Haley LuRichardson) in season two offsets this let alone the tragedy of the kooky but immensely likeable Chelsea (Aimee Lou Wood) in season three.

Underpinning all of this is a recurrent theme – effectively and fully explored – of toxic masculinity starting with the utterly irredeemable Shane in season one. He starts out by making unreasonable demands of the hotel and ends up murdering the hapless Armand whilst meantime consistently treating his new, young wife Rachel (Alexandra Daddadio) as a trophy for his mantelpiece. More to the point, he gets away with all of it, including manslaughter, and his wife returns to him at the airport. This is part and parcel of White’s scathing critique of privilege yet sets up a theme to which he will persistently return. Cameron in season two is a good looking yet arrogant man on the make embroiled in competing with his best friend whilst, more significantly, the Di Grasso family are entirely composed of three generations of varying forms of masculinity – the “it’s natural” grandfather Bert (F Murray Abraham), the “recovering” sex addict father Dominic (Michael Imperioli), and the “guilt ridden” son Albie (Adam Di Marco). Interestingly, none (quite) gets the girl. The grandfather is too old, the father misses his wife and is desperate for her forgiveness, whilst his son is duped by a sympathetically portrayed, yet on-the-make, sex worker Lucia. This moral complexity is played out in more depth in season three when the supposed archetype of successful masculinity (Timothy) unravels into a self-doubting and semi-suicidal mess that can do no more than appreciate the power of family by the end. From here, his adoring son Saxon proclaims he is nothing without what his father has given him and gradually implodes in the wake of too much admiration from his younger brother Lochlan. Thus, it would seem that – without invoking Donald Trump who is raised in conversation by the group of female friends – White concludes that the classic American ideal of masculinity is more simply a disaster waiting to happen. Such tropes resonate strongly within and across contemporary culture and account for much of the show’s success. Interestingly, alongside this, more than once White also invokes the figure of boyhood innocence in both season one when Quinn (Fred Hechinger) leaves his family to ride the waves and the whales with the other Hawaiian boat men and – in a moment of jaw wobbling emotion – Timothy, in tragically trying to spare the one “innocent” in his family, accidently near kills his son Lochlan then, in a further twist, saves him with a maternal style of love in a scene that has echoes of the Christian pieta in its presentation. It is perhaps tempting to read this in terms of the over-cooked concept of “masculinity in crisis” yet there remains a strong sense of redemption in these story lines of finding nourishment in simpler ways of living.

As is becoming evident here and is otherwise well-known, The White Lotus shows are not merely entertainment or drama, but thematically multi-layered explorations of varying issues. These both organise particular series and overlap across them. For example, season one is dominated by themes of privilege and the struggles of the have nots (the hotel and other workers) in the face of haves’ immense wealth and power (the hotel guests). If plotlines are taken to indicate “messages”, then the argument here is that privilege will always out – whether in terms of wealthy women who mislead their masseurs or money spinners who quite literally get away with murder. Similarly, waiter Kai’s (Kekoa Scott Kekumano) failure to steal Nicole’s bracelet, in an attempt to reclaim a small part of Hawaii’s heritage from greedy colonialist hands, ends in disaster whilst Armond desperately tries to secure the hotel’s reputation yet is fired anyway. What is thought-provoking here is that this could easily invoke frustration and fury for the audience yet the sense of moral complexity of both plot and character overtakes this.

Season two also interestingly inverts such outcomes as the workers, not the guests, are triumphant. The good time girls Lucia and Mia get their money, Valentina is sexually liberated, and “rent boy” Jack carries on whilst the guests all end up fleeced, corrupted, confused, or dead. At the centre of this is sex. Sex in White’s narratives is a leveller, something that can render the powerful weak and the clear-headed confused. At the centre of this in turn is identity – who exactly is zooming who? These dark and murky themes ratchet up interest for audiences who attempt to morally evaluate what they see.

The parallel with reality TV is clear as already outlined yet what is more interesting here is White’s invoking of older and deeper, more literary – and indeed cinematic – explorations. Ian McEwan’s novel The Comfort of Strangers (1981) explores the moral complexities of love and sex as a young couple find themselves victims of something more far more visceral in Venice. Its more cinematic qualities were later developed as a film of the same name by Paul Schrader in 1990. Whilst the psychological dramas of Hitchcock’s greats such as Psycho(1960) and Vertigo (1958) are easy reference points, another that underpins the third series in particular is Conrad’s turn of the twentieth century novella Heart of Darkness (1899), later the basis for Coppola’s critique of the Vietnam war in Apocalypse Now (1979), and resonant here. An exploration of the hollowness and savagery at the heart of the civilised west is, in season three, juxtaposed with the ideas and teachings of Buddhism. Whilst some characters are moved and confused – particularly Timothy, Saxon, and Lochlan – others such as Victoria are unmoved. Similarly, those representing Buddhism itself do so in very mixed ways – Sritala (Lek Patravardi) is portrayed as an egoist screaming “kill him” at the end whilst Gaitok garners his promotion and gets his girl but at huge cost to his own moral compass. Whilst some western characters become more sympathetic to Buddhism, Thai Mook for example echoes the western trope of the gold digging woman. Meanwhile, Suthichai Yoon as Luang Por Teera, a Buddhist monk, talks more sense than the rest of the cast put together. The feeling here that all is far from well in the affluent west, materially and spiritually, is vast…

This thematic “goo” of morality, corruption, and redemption – in the wake of the hollowness of western extravagant consumption on lavish holidays – makes The White Lotus a rather religious show on more than one level. Most of the major characters have lost, or are losing, their way as if to say that if organised faith fails in the wake of secularism, then other guidance is needed. This is indeed a grandiose theme yet in a twenty first century dominated so far by wars, threats of terrorism, extreme greed and need, and day to day struggles to find meaning, it is one of immense redolence. It is not surprising then that Laurie’s (Carrie Coon) paean to friendship in a long speech at dinner on how, aside from anything, we are all just on a journey with each other had most of its audience in tears.

All of this so far focuses on the show’s content, characters and plots. A final key aspect to its success centres on how it looks and sounds. Whilst the production values of many shows since the inception of pay for streaming TV globally have risen immensely, The White Lotus is perhaps in a stratospheric league of its own, only matched by that invested in the fantasy genre. There are two factors at work here. One is that the shows are all shot on location where they are narratively set and the hotels are real, using access to various Four Seasons Hotel locations. On top of this, White adds his own cinematic skill in amplifying equally the visual “wow” factor and more symbolic imagery. Hence the sea is real yet then overlaid with visual effect. In season one, Hawaii is portrayed as a water surrounded oasis, the water itself and the canoes and ocean wildlife feature strongly both visually and as a plotline for the escape of the deeply dissatisfied Quinn from the utterly dysfunctional Mossbacher family. In season two, Sicily sizzles visually as a stunning landscape for its characters yet White adds recurring motifs through his use of murals, artwork, ornamentation and decoration of Greco-Roman style mythology – frescoes, paintings, and Mount Etna all feature – to illustrate the risks the charters face. The effect, as in the visit of Daphne and Harper to a luxury ancient villa or in Tanya’s stay at Quentin’s mansion in Palermo, is to increase anxiety – or the spooky factor – in the onlooker. More particularly, it plays into White’s handling of the death of Tanya that, directly and indirectly, is intentionally “operatic”. She is taken to the stunning Teatro Massimo in Palermo to watch perhaps the most “tragic” and “heroine” centred of all operas, Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. Operas are well-known for their tragic heroines and contorted plotlines, and it is this, rather than any verisimilitude of “reality”, that explains the convolution of the show’s core story. Similarly, yet more so, season three sees Thailand awash with monkeys, snakes and lizards as well as verdant trees and shrubbery that themselves seem almost alive in what is clearly intended as a semi-pantheistic invocation of humans lost in nature. The settings and their presentation echo the themes of the show and the internal worlds of the characters – the monkeys that chatter and disrupt, the sexualisation of the scenery that offers both possibilities to hide and be seen, and the ocean that constantly threatens to drown all in uncontainable emotion. White’s skill here is perhaps unparalleled. For example, in one of the key scenes of series three, a monologue by Frank (Sam Rockwell), heard and watched aghast by Rick, on the confusion of desire and identity of wishing to actually “be” a Thai girl fucked by his more masculine self, is set in a bar awash with glassy golden yellow walls and blurred shadow imagery that alludes to both problems of alcoholism and the moral ambiguity, if not even collapse, of the characters involved. The scene was overly simplistically interpreted an exploration of Blanchard’s controversial conceptualisation of autogynephilic transsexualism yet is more accurately a study of the breakdown of Western identity in the face of challenges from more Eastern traditions and practices. All shows in the series, as a matter of course, employ a more cinematic level of mise-en-scène with, for example, hotel décor echoing artwork used in the opening credits alongside a wider, hefty use of nature-based symbolism throughout.

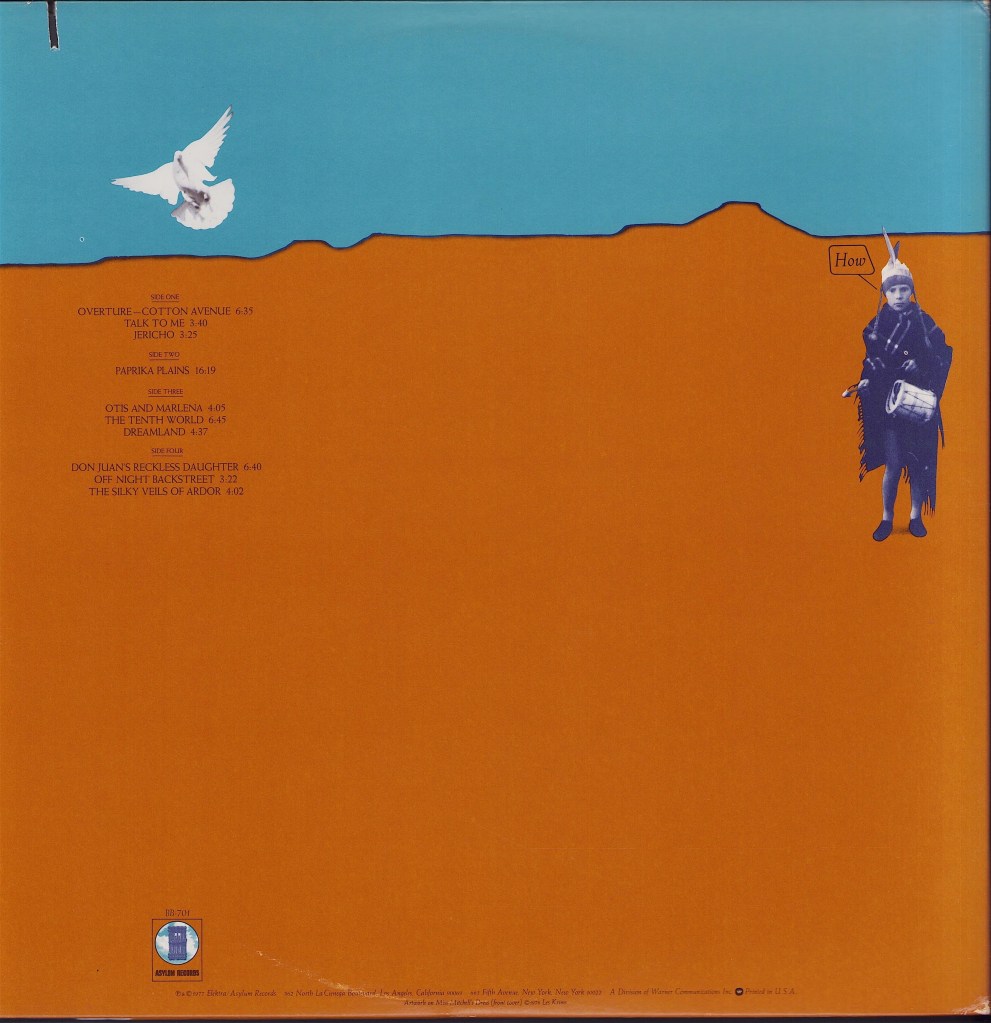

A similar statement may be made about White’s use of music in the show. Working with long-time collaborator and musician Cristóbal Tapia de Veer, they come up with both theme tunes and sound effects playing on those theme tunes that play a large part in upping the “creepiness” and tension of many scenes. Season two is littered with the use of classically Italian love songs – for example, Dean Martin’s That’s Amore sung at one point by Mia at the piano – yet Cristobal is Chilean Canadian and draws on a perplexing mix of both South American rhythmic and downright weird sound effects that often echo nature, animals, rhythms and disturbances. In season two they are routinely paired with the imagery of mythology, art, and Italian frescoes to somewhat operatic “screaming” effect on occasion; whilst in season three, the music – prominent to the point of intrusiveness perhaps – adds to key scenes of character interiority and plot. The repetitive and weirdly “breathy” refrain that is used in season three repeatedly occurs when risks of death are invoked, for example, in Timothy’s “not so pina colada” shake-making and delivering. Whilst music is commonly used in TV shows, the level at which it is pitched here is more cinematic – akin to key scores such as say the use of Michel LeGrand’s piano in juxtaposition with imagery of deadly nightshade in Losey’s seventies classic The Go-Between (1971). Such a parallel in technique is not unfounded for the image and substance of the white lotus is constantly juxtaposed literally and symbolically with that of belladonna or deadly nightshade (even to the point of Timothy’s use of the cerbera odollam or “pong pong” fruit in season three). Whilst the white lotus flower often represents spirituality, purity and transformation or reincarnation, belladonna symbolises not only literal death but desire, self-destruction, and implosion. It is difficult to conceive of a more potent juxtaposition of imagery that, together with its complex plotting and character development, stirring of contemporary morals and profound thematic concerns, makes The White Lotus unmissable and resonant TV.