Toxic masculinity is a con trick of a concept that deflects attention away from the causes of some men’s behaviour and which obscures wider and deeper explanations of what is happening. Concerns relating to masculinity have inculcated a string of mediatised terminology over some decades – from the new man to new lad and from the metrosexual to the existential, or not, crisis of masculinity. As I have attested elsewhere (Edwards 2006) the latter idea is a woeful muddle – are all or some actual men in crisis and if so a crisis of what, self-esteem or poverty; or is masculinity as set of ideas sticky note posted to males in some kind of disarray, devalued, or negative? Or all of this? The haze is closer to a complete fog. And some historians have queried whether this already dated idea is new at all (Kimmel 1987). Whilst the origins of metrosexual terminology are reasonably clear given Mark Simpson’s postulating of a description of metropolitan narcissism in the 1990s (Simpson, 1994) the rest is frankly a muddle. And a mediatised muddle. So, we shift from discussing David Beckham’s fashion sense to the now near defunct Loaded lifestyle magazine, and – as of this month – BBC documentaries concerning the internet “manosphere”. James Blake presents this. A bit of a hottie if you ask me – and not surprising he is used here – not to be confused with the singer songwriter he’s rather a TV presenter in the style of Stacey Dooley for BBC3. Such TV amps up the concern, or more cynically hysteria, over issues to get ratings and attention – and there’s clear inflexion of the North American in this which is whence the mythopoetic men’s movement and wider polemics on “the crisis” come (Bly, 1991). Even women, North American ones, get in on the act so Susan Faludi’s critique of an anti-feminist “backlash” is resurrected in the wake of her volte face concern with “stiffed” men (Faludi, 1992, 2000).

Yet my cynicism here masks a deeper concern for this is not simply mediatised nonsense. David Szalay has recently won the (was “Man”) Booker prize with his novel Flesh (Szalay, 2025). It tells the tale of István, a Hungarian teenager then man whose life blows along rather like paper bag in the wind from disaster to success and back again. Anchoring it are references to sex, his physical-ness, as a constant given his psychological and emotional life are deeply repressed, hidden even, through the flat yet close third person narration. He does “bad” things, such as – in the first instance – getting into a fight and accidentally killing someone following his emotionally confused affair with an older woman. Or rather one might say oppressed given it is the woman who refuses his declarations of love. Szalay’s highly accomplished writing performs certain tricks – first that we learn things late, or suddenly, in offhand ways – such as his loss of a friend in the Iraq war or indeed that he fought in the Iraq war – whilst the chapters, long but pacy, are separated by blank pages where one learns in the next one that István is somewhere different but we have no tale of how he got there. It’s ingenious. It’s also symbolic and, if you allow it to, it will reduce you to near tears as – as they say – it’s all in what’s not said not what is. What it symbolises and expresses is key to my concern here.

The Guardian, doing what the Guardian does, has latched onto the novel as a description of “toxic masculinity” and Szalay has spoken openly of his jitters concerning such as it were “woke” interpretations. Yet toxic masculinity fails to explain the story of a fictional Hungarian let alone where men are at whilst the novel itself has a lot to say about life in the twenty first century. I will return to this. The toxic masculinity story, meantime, goes as follows. Young (in particular) men are turning to the online manosphere and antifeminist rhetoric if not practice as masculinity is in crisis. They seek toxic masculinity – hard, repressed, anti-feminist, aggressive, misogynist – as a solution when what they need is good male role models. Interestingly, metrosexual Beckham is a primary example, good looking, in touch with his feminine side, a family man, pro-gay, etc. Except he is silly level wealthy. What also feeds into this is the wider concern with the influences of social media and the internet, the same neurosis that underpins a myriad of parental led campaigns about children needing protection from pornography, unrealistic imagery, bullying, and hate speech from the likes of Andrew Tate. Tate is a media star, or near avatar, of what one might call “anti-woke” sentiment from promoting money making and kick boxing to misogynist and homophobic commentary or “advice” given through social media platforms. Similarly emblematic of this “toxic masculinity” is Donald Trump who needs no introduction. The solution it is argued, lies in countering the anti-woke with woke – the homophobic with the pro-gay, the anti-feminist with the pro-feminist, and so on – and for young men to have better role models. Parsons – him of the nuclear family system where men are instrumental and women are expressive (this is their “function” as “socialisers”) – would be proud (Parsons, 1949).

Let us get back to Szalay’s novel. Implicit in this, if not explicit, is a critique of the neoliberal agenda which reduces our lives to a model of individual choice. As sociologists and others well know, this is patently false. You cannot choose a big house, to drive a fancy car, or even get the means to either if you are poor, live in the wrong place, and can’t even get the education. Decisions are social and structural not willy nilly expressions of an inner moral compass. Such whims were repeatedly given legs via the “it’s your fault if you are poor” understanding – or rather ideology – of poverty that has existed for centuries. Margaret Thatcher, and a host of others, gave it arms, a head, and a heart to run with – so the poor(er) blame themselves, feel guilty, and get stigmatised nonstop by the world around them. Bauman has blasted this apart repeatedly as we are either “repressed” and cannot have that which society deems normal or we are “seduced” into consumerist addiction trying to get it (Bauman, 1998). Similarly, István’s emotional autism – or more simply numbness – is perhaps better explained as a shutdown to the pain inflicted upon him rather than some inner psychosis.

Toxic masculinity is not even a psychological condition. It does not exist outside of media, and “impact” hunting academia, at all. Yes, some men – Trump, István – do horrible things but we are avoiding where they are getting it from. The recent Eastenders story line of how a teenage boy ends up hospitalising his stepmother due to the “dark web” of the “manosphere” similarly distracts. He is poorly educated and working class and – more to the point – neither parent is properly capable of emotionally communicating with him. Similarly, Kat Slater struggles with her son but makes a better job of it. Yes, individual upbringings come into it but diffuse, confused terminologies of gender and masculinity evade the all too obvious consequence that this is what happens when there is no job security, too many have too little opportunity, and there is no safety net in too many cases. And, alternatively, others become populist narcissists drunken and deluded to the point of criminality on their own grandeur. Guess who. In either case, the issue is the lack of infrastructure of any kind to keep this in check. Late, high – or whatever terminology you want to give it – capitalism, as premised upon neoliberalism, defined as a “rolling back” of state provision whilst increasingly using the state’s legislative powers to control and oppress all and any forms of opposition to it, is key. Hence the polity collapses into the economy and politicians are entrepreneurs and the shots are called by global CEOs. Seeing Trump, or whoever, as an outcome of “toxic masculinity” is – as if to pull down a veil – to miss the point.

The other side of this conundrum is women, or rather femininity, or rather again “commodity feminism”. Goldman and his colleagues coined the term in the 1990s and they and others have extrapolated upon it since (Gill, 2008; Goldman, 1992; Goldman, Heath & Smith, 1991). The term is a play upon the Marxist concept of commodity fetishism or the ways in which the marketized values given to commodities mask their significance as the products of capitalist relations. Goldman initially illustrated this through an analysis of a late 1980s advert for the VW Golf car where a woman dumps the fur coat, the ring, and other symbols of “male” ownership and heterosexuality yet keeps the car (and her independence). Thus, the concept has primarily focused upon Marxist or neo-Marxist studies of advertising and consumer culture. Baudrillard’s extensive analysis of the collapse of all social meaning into the “commodity form” also underpins much of this (Baudrillard, 1993, 1998). Put simply, feminism and more populist ideas of women’s empowerment are, as it were, “co-opted” to sell stuff.

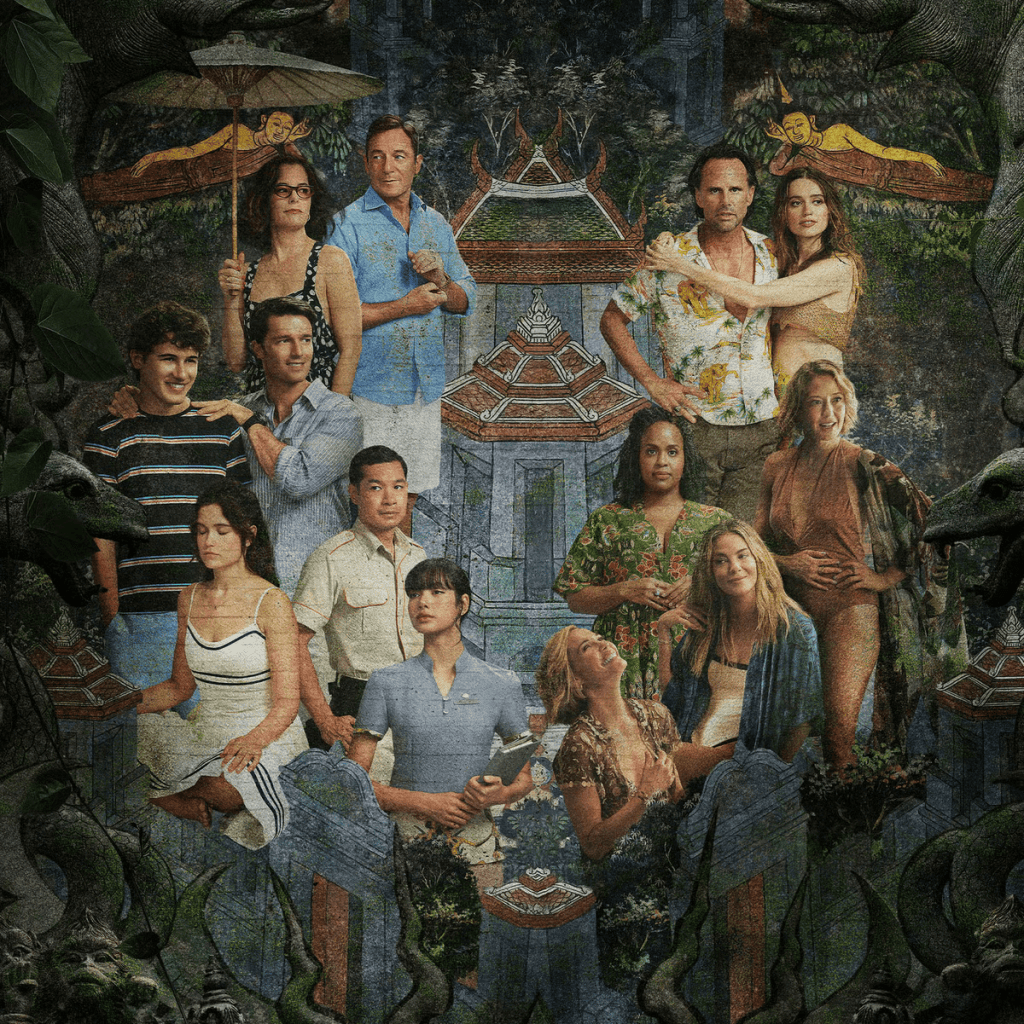

My point here is this process has expanded and developed to a point where it saturates the entire mediatised world of popular culture. Women’s empowerment is now less a statement on their oppression and more a commercial slogan underpinning everything from TV programming to music, film, and media analysis more widely as it “chimes in” with the wider theme of “woke” politics as already outlined. Examples of this proliferate exponentially from the music of Sabrina Carpenter and Taylor Swift, to more or less all TV shows featuring Suranne Jones, let alone the legion of soap operas and dramas dominated by female interest story lines. The legacy of the likes of Sex & The City and Desperate Housewives let alone Killing Eve or The Handmaid’s Tale is immense here. The attempt to represent female empowerment against the odds, or indeed toxic masculinity, is at near epidemic levels in the UK with – in particular – an endless string of mini-TV series involving increasingly fantastical plotlines centred on gender (The Guest – where a poor white female thwarts a rich white male with the support of a rich white female is a recent prime example).

Presenting women as strong female leads is important in counteracting the centuries old legacy of the male gaze as famously outlined in the work of Laura Mulvey – men do stuff and women get looked at – yet, more insidiously, the attempt to challenge this has become co-opted into some marketized con-trickery where women suddenly get away with murder, sometimes literally (Mulvey, 1975). This deflects attention away from the empirical realities where, whilst much has improved, women are not equal in the workplace, remain the targets of violence and abuse, and are still – or perhaps even more – judged on their appearance.

Toxic masculinity turns much of this on its head to assert that hegemonic culture is increasingly female-centric and excludes, devalues, and misrepresents men. There is a point of sorts here – for example, Mr Muscle whether as advert or wider representation, plays upon a trope of men as simply useless – yet it’s less this issue of (mis)representing masculinity that is at stake here rather the fact that it obscures the structural oppression of women and systemic gender inequality as a mechanism that underpins the lives of men and women alike. There’s no lack of positive images of masculinity around from athletes to pop stars, film stars and characters to more politically conscious businessmen, or David Attenborough. Thus, whilst discussions and critiques of toxic masculinity appear to empower women and feminism, or highlight men’s suffering and needs for support, they effectively deflect the entire portrayal of gender relations into a marketing device to promote a TV show, a car, or popular culture more widely.

This is easily read as a sort of clumsy Marxist critique of capitalism, yet it is more a statement on its contemporary hyper consumerist, hyper individualised, and mediatised form. We are constantly encouraged to view any and every difficulty through the lens of a neoliberal model that renders all and sundry not only as individual rather than structural but as a mediatized, consumerist, “topic” to market, sell, or even discuss in limited terms. In turn, this is not new yet centred on the de-regulation of markets to include so that everything from soap powder to spiritual awakening could be “sold” – hence “pink washing”, or slap a rainbow on a jar of marmalade to make out the manufacturer is a supporter of LGBTQ rights, or similarly “greenwashing” where terms such as sustainability and fair trade are thrown around with such wild abandon to incorporate everything from coffee plantations to polyester (yes, really) they become utterly meaningless and reduced to mere marketing tactics. Thus, here men’s violence against women becomes the focus of selling a TV show or a discussion point in the press on “toxic masculinity”. As Richard Dyer once wrote, masculinity is rather like air, constantly there but almost impossible to see (Dyer, 1993). It’s also now increasingly another mediatised concept that confuses discussions of how people, and perhaps particularly some groups of men, are just plain lost.

The more appropriate concept of use here is, perhaps surprisingly, Durkheim’s idea of anomie. Anomie relates to a state of normlessness, of difficulties in knowing right from wrong, or just making decisions, a lack of social glue… He highlighted not simply the decline of organised religion or rise of science and secularisation here, rather the shift in solidarity (the glue) holding society together as we moved from a world of commonality and sameness into one of complexity and difference. It’s an idea that points towards the impact of globalisation and its contradictory tendency to promote diversity whilst collapsing into a McDonald’s in every country. For the factor missed here is that diversity is itself a strategy of selling what critical Marxists called pseudo-individuality (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1973). Or, to put it another way, a string of detergents that take up an entire aisle in the supermarket yet are owned by a mere two companies when all do the same thing as stuff to stick in your washing machine.

Let us return to István. Istvan’s decisions and life course centre on the need for immediate gratification, yet rather than greed what this implies is simply an issue of survival – of finding the means to live and enjoy stuff at least some of the time. His education and situation are poor – his assets are physical and fleshy – he is strong, can fight, and work as a bouncer, or get sex in an opportunistic sort of way – women seem to fancy him and come on to him. His life blows along, as I have said, like a brown paper bag in the wind, from Hungary to the Iraq war to London security firms and dodgy dealers, from rags to riches and back again. What punctuates this is his sexual relationships with women and his physicality. This is the one constant, hence Flesh. The story turns full circle.

He commits occasional acts of violence and is near monosyllabic throughout – an implied autism perhaps – saying “OK” to nearly everything. To read him as an example of toxic masculinity, however, is way off point. His wealth extends from an act of gallantry, he does not shirk work, and clearly loves his son, whom he loses suddenly. He is alienated and lonely. He also remains devoid of assets that are his own. The issue, to return to where I began, is that life happens to him not him to life. His life course is almost entirely not under his control and extends from consequences he cannot see. As such, it is a damning indictment of the neoliberal maxim, or bullshit, “life is what you make it”. It’s also believable – resonating as a tale of anybody who is nobody – which is precisely the point. Concepts such as toxic masculinity do not explain István, men in general, or the twenty first century. They are a gross – and arguably deliberate – distraction from what is in plain sight. Shit happens – to some, mostly poorer, people more than others – and rarely through much fault of their own. Others profit, lie on sun loungers and rip off everyone else largely because they can, and they get lucky. We laugh at them in thrillers on TV where they seem to come unstuck, note seem. This is, in essence, the nature of the twenty first century. Not chromosomes.

References

Adorno, T. W. & Horkheimer, M. (1973) Dialectic Of Enlightenment, London: Allen Lane.

Baudrillard, J. (1983) Simulacra And Simulations, New York: Semiotext(e) (orig. pub. 1981)

Baudrillard, J. (1998) The Consumer Society: Myths And Structures, London: Sage (orig. pub. 1970).

Bauman, Z. (1998) Work, Consumerism And The New Poor, Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bly, R. (1991) Iron John: A Book About Men, Shaftsbury – Dorset: Element.

Dyer, R. (1993) The Matter Of Images: Essays On Representation, London: Routledge.

Edwards, T (2006) Cultures of Masculinity, London: Routledge

Goldman, R. (1992) Reading Ads Socially, London: Routledge.

Goldman, R., Heath, D., & Smith, S. L. (1991) “Commodity Feminism” in Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8(3), pp. 333–351.

Faludi, S. (1992) Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women, London: Vintage.

Faludi, S. (2000) Stiffed: The Betrayal Of Modern Man, London: Vintage.

Kimmel, M. S. (1987) “The Contemporary ‘Crisis’ Of Masculinity In Historical Perspective” in H. Brod (ed.) The Making Of Masculinities: The New Men’s Studies, London: Hutchinson

Mulvey, L. (1975) “Visual Pleasure And Narrative Cinema” in Screen, 16, 3, pp. 6-18.

Parsons, T. (1949) “The Social Structure of the Family” In R. N. Anshen (ed.), The Family: Its Function and Destiny, NYC – New York: Harper (pp. 173–201)

Simpson, Mark (1994) “Here Come the Mirror Men”, The Independent, 15 November

Szalay, D. (2025) Flesh, London: Jonathan Cape.